Oscar Stanton De Priest’s Lonely Fight

A campaign button for De Priest

A campaign button for De Priest

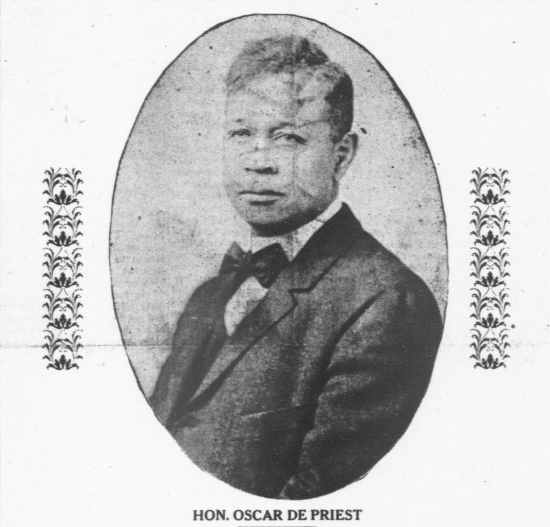

Our next profile examines the life and legacy of Oscar Stanton De Priest, an American lawmaker and civil rights activist who became the first African-American not from a southern state to be elected to Congress after a 27 year interval.

Oscar Stanton De Priest was born on March 9, 1871 in Florence, Alabama to parents who were freed former slaves. His mother, Martha, held a part-time job as a laundress, while his father was a teamster associated with the “Exodus” movement, the first general migration of blacks following the Civil War. Like many blacks moving from the South to the North in search of greater freedom and opportunity, the De Priests relocated to Dayton, Ohio following violence from lynch mobs within their local community.

De Priest moved to Salina, Kansas, where he attended the Salina Normal School and studied bookkeeping, and eventually ended up in Chicago, Illinois, where he held a variety of positions, from house painter and decorator to real estate broker. He slowly built up a fortune through the stock and real estate markets by assisting black families move into formerly white neighborhoods. Between 1915 and 1917, he was the first black man to serve on the Chicago City Council as the alderman of the 2nd Ward.

In 1919, De Priest ran for alderman of a political organization called the People’s Movement Club, which he founded. Although he did not win the bid, he became one of the most important and influential politicians under the then Republican mayor of Chicago, William Hale Thompson. In 1928, when the Republican congressman Martin B. Madden died suddenly, Mayor Thompson backed De Priest to replace Madden’s name on the ballot, marking his formal entry into state politics. He became the first African-American elected to Congress in the 20th century, representing the 1st Congressional District of Illinois as a Republican.

De Priest’s arrival in Washington made headlines. One particular instance occurred after First Lady Lou Hoover invited his wife to tea at the White House along with all of the Congressional wives. Southern politicians erupted in response to this: multiple state legislatures passed resolutions imploring President Herbert Hoover to give, as Mississippi put it, “careful and thoughtful consideration to the necessity of the preservation of the racial integrity of the white race.” Averting a threatened boycott of the event by Southern Congressmen’s wives, Mrs. Hoover held four separate receptions—the one Mrs. De Priest attended being the smallest. De Priest defended his wife, telling the newspapers, “I’ve been elected to congress the same as any other member,” he exclaimed. “I’m going to have the rights of every other congressman—no more and no less—if it’s in the congressional barber shop or at a White House tea.”

Another example of the discrimination De Priest faced involved the Capital facilities themselves. One of his most famous fights was trying to desegregate the whites-only restaurant in the House of Representatives after one of his African-American aides was denied service there—a case that was taken to a special bipartisan House committee. De Priest said of the incident, “If we allow segregation and the denial of constitutional rights under the Dome of the Capitol, where in God’s name will we get them?” He added that, “If we allow this challenge to go without correcting it, it will set an example where people will say Congress itself approves of segregation.”

In the decision, the Republican minority argued that, according to the 14th Amendment, the restaurant should not be allowed to implement its segregation policy. Unfortunately, Democrats countered that argument with the claim that the restaurant was not open to the public and therefore was not subject to the 14th Amendment. The House restaurant, despite De Priest’s efforts, remained segregated.

De Priest would go on to serve three consecutive terms (1929-35) as the only black representative in Congress. As such, he felt a responsibility to represent all African-Americans, nationwide. In that capacity during his time in office, he advocated for and introduced numerous anti-discrimination bills. Like George Henry White before him, he attempted to pass an anti-lynching bill that would have held local jurisdictions accountable for occurrences. He also advocated for reduction—reducing the number of representatives from states where black voters were disfranchised. He also attempted a reparations bill that would have given pensions to seniors who were former slaves. In response to an infamous case in Scottsboro, Alabama where nine black youths were sentenced to death by an all-white jury for raping two white women despite evidence to the contrary (which would later became an example of the travesties of the justice system), De Priest introduced a bill allowing for a transfer of jurisdiction if a defendant believed he or she was not receiving a fair trial because of race or religion. In 1931 he also introduced legislation to make President Abraham Lincoln’s birthday a federal holiday. None of these bills were passed.

De Priest did have some legislative success, such as an amendment that banned discrimination in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which was passed as part of the bill and was signed into law by President Franklin Roosevelt. De Priest described his work on discrimination, saying, “I am making these remarks because I want you to know that the American Negro is not satisfied with the treatment he receives in America, and I know of no forum where I can better present the matter than the floor of Congress.” He also successfully nominated black candidates for enrollment at military academies. Additionally, De Priest was praised for continuing his speaking engagements in the South despite persistent threats against his life.

In the early 1930s, De Priest’s stance against federal relief during the Great Depression and increased taxes on the nation’s rich caused his popularity to fall. He was defeated in the 1934 Congressional election by Arthur W. Mitchell, an African-American Democrat, but was once again elected to the Chicago City Council in 1943, a position he held until 1947. However, his former seat from the 1st Congressional District of Illinois continued to be occupied by African-Americans up through the present day—for a time, sending the only black person to Congress.

De Priest died at the age of 80 in Chicago and is buried in the Graceland Cemetery. His house in Chicago is considered a National Historic Landmark.

Oscar Stanton De Priest made incredible strides for his time period, working for legislation that would benefit blacks around the country. Despite the difficulties he faced, he set a courageous precedent for all Americans, both within the political world and outside of it, to strive for equality and fight for their beliefs.

Oscar Stanton De Priest was born on March 9, 1871 in Florence, Alabama to parents who were freed former slaves. His mother, Martha, held a part-time job as a laundress, while his father was a teamster associated with the “Exodus” movement, the first general migration of blacks following the Civil War. Like many blacks moving from the South to the North in search of greater freedom and opportunity, the De Priests relocated to Dayton, Ohio following violence from lynch mobs within their local community.

De Priest moved to Salina, Kansas, where he attended the Salina Normal School and studied bookkeeping, and eventually ended up in Chicago, Illinois, where he held a variety of positions, from house painter and decorator to real estate broker. He slowly built up a fortune through the stock and real estate markets by assisting black families move into formerly white neighborhoods. Between 1915 and 1917, he was the first black man to serve on the Chicago City Council as the alderman of the 2nd Ward.

In 1919, De Priest ran for alderman of a political organization called the People’s Movement Club, which he founded. Although he did not win the bid, he became one of the most important and influential politicians under the then Republican mayor of Chicago, William Hale Thompson. In 1928, when the Republican congressman Martin B. Madden died suddenly, Mayor Thompson backed De Priest to replace Madden’s name on the ballot, marking his formal entry into state politics. He became the first African-American elected to Congress in the 20th century, representing the 1st Congressional District of Illinois as a Republican.

De Priest’s arrival in Washington made headlines. One particular instance occurred after First Lady Lou Hoover invited his wife to tea at the White House along with all of the Congressional wives. Southern politicians erupted in response to this: multiple state legislatures passed resolutions imploring President Herbert Hoover to give, as Mississippi put it, “careful and thoughtful consideration to the necessity of the preservation of the racial integrity of the white race.” Averting a threatened boycott of the event by Southern Congressmen’s wives, Mrs. Hoover held four separate receptions—the one Mrs. De Priest attended being the smallest. De Priest defended his wife, telling the newspapers, “I’ve been elected to congress the same as any other member,” he exclaimed. “I’m going to have the rights of every other congressman—no more and no less—if it’s in the congressional barber shop or at a White House tea.”

Another example of the discrimination De Priest faced involved the Capital facilities themselves. One of his most famous fights was trying to desegregate the whites-only restaurant in the House of Representatives after one of his African-American aides was denied service there—a case that was taken to a special bipartisan House committee. De Priest said of the incident, “If we allow segregation and the denial of constitutional rights under the Dome of the Capitol, where in God’s name will we get them?” He added that, “If we allow this challenge to go without correcting it, it will set an example where people will say Congress itself approves of segregation.”

In the decision, the Republican minority argued that, according to the 14th Amendment, the restaurant should not be allowed to implement its segregation policy. Unfortunately, Democrats countered that argument with the claim that the restaurant was not open to the public and therefore was not subject to the 14th Amendment. The House restaurant, despite De Priest’s efforts, remained segregated.

De Priest would go on to serve three consecutive terms (1929-35) as the only black representative in Congress. As such, he felt a responsibility to represent all African-Americans, nationwide. In that capacity during his time in office, he advocated for and introduced numerous anti-discrimination bills. Like George Henry White before him, he attempted to pass an anti-lynching bill that would have held local jurisdictions accountable for occurrences. He also advocated for reduction—reducing the number of representatives from states where black voters were disfranchised. He also attempted a reparations bill that would have given pensions to seniors who were former slaves. In response to an infamous case in Scottsboro, Alabama where nine black youths were sentenced to death by an all-white jury for raping two white women despite evidence to the contrary (which would later became an example of the travesties of the justice system), De Priest introduced a bill allowing for a transfer of jurisdiction if a defendant believed he or she was not receiving a fair trial because of race or religion. In 1931 he also introduced legislation to make President Abraham Lincoln’s birthday a federal holiday. None of these bills were passed.

De Priest did have some legislative success, such as an amendment that banned discrimination in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which was passed as part of the bill and was signed into law by President Franklin Roosevelt. De Priest described his work on discrimination, saying, “I am making these remarks because I want you to know that the American Negro is not satisfied with the treatment he receives in America, and I know of no forum where I can better present the matter than the floor of Congress.” He also successfully nominated black candidates for enrollment at military academies. Additionally, De Priest was praised for continuing his speaking engagements in the South despite persistent threats against his life.

In the early 1930s, De Priest’s stance against federal relief during the Great Depression and increased taxes on the nation’s rich caused his popularity to fall. He was defeated in the 1934 Congressional election by Arthur W. Mitchell, an African-American Democrat, but was once again elected to the Chicago City Council in 1943, a position he held until 1947. However, his former seat from the 1st Congressional District of Illinois continued to be occupied by African-Americans up through the present day—for a time, sending the only black person to Congress.

De Priest died at the age of 80 in Chicago and is buried in the Graceland Cemetery. His house in Chicago is considered a National Historic Landmark.

Oscar Stanton De Priest made incredible strides for his time period, working for legislation that would benefit blacks around the country. Despite the difficulties he faced, he set a courageous precedent for all Americans, both within the political world and outside of it, to strive for equality and fight for their beliefs.