The End of an Era: George Henry White

George Henry White was born December 18, 1952 in Rosindale, North Carolina to Wiley Franklin White, a free man of African, Scots-Irish and Native American ancestry, and a slave named Mary. The second son from the union, it is believed that Wiley bought George and his brother John’s freedom (the rule at the time stated that if the mother was a slave, her children were born slaves). Five years later he married May Anna Spaulding and the Whites moved to Columbus County.

Education would become an important value for White, even though his first educational experience was most likely in a local subscription school, which tended to be under-resourced and in session for short durations. However, after the Civil War, public schools were established for black students and White ended up attending the Whitin Normal School, due to the encouragement of teacher David Allen. In 1974 he matriculated at Howard University in Washington, D.C, which had been established seven years prior as a college open to students of all races. While there he worked to be certified as a schoolteacher, finishing in 1877.

Returning to North Carolina having received his degree, he was hired as a principal at a black school. Concurrently, he studied law under former Superior Court Judge William J. Clarke, gaining admittance to the North Carolina Bar in 1879. That same year, he married Fannie B. Randolph, although she died a year later soon after giving birth to a daughter Della.

In that same year, 1880, White entered politics when he won a seat in the North Carolina House of Representatives representing Craven County. There he turned his attention to education, passing laws to establish four state normal schools to train black teachers, one of which he became principal of in 1881. In 1884, two years after his term ended, he ran for the North Carolina Senate and won. Two years after that, White was elected solicitor and prosecuting attorney for the Second Judicial District, a six-county area.

In the same year, he married Cora Lena Cherry, whose sister was married to Henry Plummer Cheatham, who would become a political rival. Cheatham had been born into slavery and worked after emancipation to establish public schools for black children. After working as a principal, Cheatham was elected Register of Deeds for his county in 1884, beginning his political career. Four years later he was narrowly elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

In the House, Cheatham supported federal aid for education and the McKinley Tarriff, which greatly increased the taxes on imported goods. He also supported a Federal Elections Bill, which would have safeguarded the voting rights of African-Americans in the South through federal enforcement. Unfortunately, the bill passed the House but died in the Senate. In 1890 White considered a run for Congress against Cheatham, but deferred to his brother-in-law instead.

While Cheatham retained his seat, the Democrats did well nationally, re-taking the House, which meant that any legislation that benefited blacks or protected their rights would not be possible for the session. Cheatham was the only black congressman in the 52nd Congress. Still, he worked toward provisions to help the struggling economy in his district, working on legislation to protect farmers and restrict the commodities and futures markets.

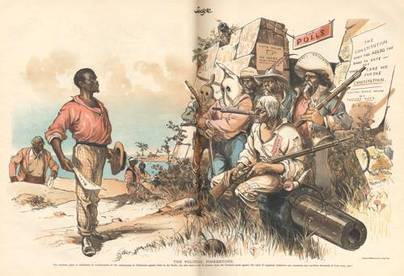

A Harper’s Weekly cartoon from the 1892 presidential election depicting the impediments to black men voting

A Harper’s Weekly cartoon from the 1892 presidential election depicting the impediments to black men voting

Starting in 1885, Democratic state legislatures across the South began enacting rules at the state level and in their constitutions to disfranchise blacks or revoke their right to vote. The strategies included white primaries (primary elections where only whites were allowed to vote), subjective literacy tests, poll taxes or requests for specific documentation proving birthplace and heritage, which were difficult for many to obtain. These impediments not only restricted blacks from voting, but prevented poor whites from voting as well. Between 1885 and 1908 every former Confederate state passed a new constitution that included these types of voting restrictions, including North Carolina.

In 1894, Cheatham and White ran against each other for the Republican nomination. It was a contentious race with both men claiming the party nomination for a time. Ultimately, the Republican National Committee decided the result in a hearing, supporting Cheatham. However, without Populist support he lost the general election to the incumbent Democrat Frederick Woodard.

Two years later in 1896 Cheatham and White ran again for the Republican nomination in the 2nd Congressional District. White defeated Cheatham in the primary and then Woodard in the general. He benefited from the recent repeal of certain laws restricting black voting by the state legislature and from a Democratic-Populist candidate who served as a spoiler for Woodard. Upon arriving in congress, White voted to protect the local timber industry with tariffs and supported the Spanish-American War and annexation of Hawaii-generally following in line with the Republican Party positions. However, the plight of African-Americans was central to his work. Among his failed efforts were an attempt to gain support for a widow whose husband and infant were lynched and trying to commission an all-black artillery unit in the Army.

In 1898 though he handily won the Republican nomination, he faced a four-way race in the general: in addition to White and the Democratic candidate, there were two Populist candidates, one whose platform included white supremacy. Despite the violent Red Shirts coming up from South Carolina to intimidate black voters, he was reelected amidst the confusion, becoming the last African-American elected to Congress from the South until 1972 and the last one from North Carolina until 1992. In Wilmington, the largest city in the state, white supremacists attempted to incite a race riot in response to his victory in an attempt to seize the city government. 11 black men were killed as a result.

Upon White’s return to Congress after the uprising, he felt an urgency to address the situation of African-Americans in the South. He consistently brought discussions back to disfranchisement, regardless of the topic. With the Federal Elections Bill having languished and no chance of gaining federal enforcement of provisions of the 15th amendment, White instead advocated reduction or having the number of representatives from Southern states in Congress reduced. Since in the House the number of representatives from a given state is determined by population, reduction held that states where black voting was being restricted should have the number of representatives reduced proportionately. In a speech to the House White stated, “If we are unworthy of suffrage, if it is necessary to maintain white supremacy…then you ought to have the benefit only of those who are allowed to vote, and the poor men, whether they be black or white, who are disfranchised ought not go into representation of the district or the State.” There were multiple reduction bills over this time period and well into the 20th century, however none of them became law.

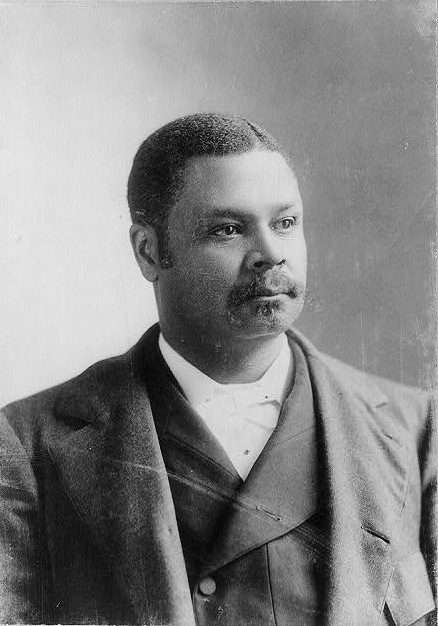

White’s portrait from NAACP magazine Crisis after his death

White’s portrait from NAACP magazine Crisis after his death

That same year, he announced that he would not seek reelection and that he was leaving the state, saying, “I cannot live in North Carolina and be a man and be treated as a man.” His support in the district had waned, partially due to white Republicans seeing his lynching and reduction legislation as inflammatory. Additionally, North Carolina had taken further measures to restrict black voting. Lastly, during the Republican National Convention, anti-lynching and black voting protections were both rejected from being incorporated into the party platform. Presaging the coming Great Migration, when six million blacks would relocate from the South between 1910 and 1970, he encouraged his fellow African-Americans to move either north or west to escape from the indignities of the South and give their children a better education.

After his term was up, he to Washington, D.C. and opened a law practice. He also founded and organized a planned African-American community on 1,700 acres in New Jersey, which was named Whitesboro in his honor. Booker T. Washington and Paul Laurence Dunbar were also involved with the venture, which grew to more than 800 people by 1906 and still exists to this day. He later moved to Philadelphia, starting the People’s Savings Bank to be a financial institution serving black customers, and became an early member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, founded in 1908. Ultimately, he rejoined politics: first with an unsuccessful bid for the Republican nomination for a seat from Pennsylvania in the House in 1912 followed by being appointed city solicitor of Philadelphia in 1917. He passed away the following year in 1918.

George Henry White was a zealous advocate for the African-American community in the South and the people of North Carolina. Sadly, much of his work came to naught due to the politics and prevailing attitudes of his time. Still, his efforts to preserve voting rights, to fight lynching, to make his state a more equitable place—for “justice-simple justice” as he once said—resound now showing him to be a man ahead of his time. When White gave his final address to the House on January 29, 1901, an emotional and inspiring speech, he predicted that things would change and defended his work on behalf of African-Americans, stating:

|

“This, Mr. Chairman, is perhaps the Negroes’ temporary farewell to the American Congress, but let me say, Phoenix-like he will rise up some day and come again. These parting words are in behalf of an outraged, heart-broken, bruised and bleeding, but God-fearing people; faithful, industrious, loyal people—rising people, full of potential force.

Mr. Chairman, in the trial of Lord Bacon, when the court disturbed the counsel for the defendant, Sir Walter Raleigh raised himself up to his full height and, addressing the court, said, “Sir, I am pleading for the life of a human being.” The only apology that I have to make for the earnestness with which I have spoken is that I am pleading for the life, the liberty, the future happiness, and manhood suffrage for one-eighth of the entire population of the United States.” |