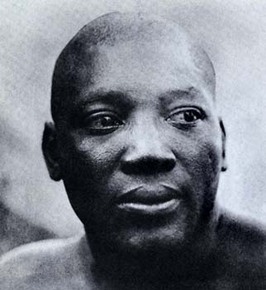

Emerging in a period when white boxers often refused to fight black boxers, Jack Johnson managed to become heavyweight champion through his superior boxing and force of will.

In 1903, having won the Negro heavyweight crown he was declared the best black boxer alive. That same year, the (white) world champion Jim Jeffries declared that he would never fight a “negro” and retired two years later citing a lack of competition—white competition. During Jeffries’ retirement Johnson began establishing himself as a force, going undefeated in 1906 and 1907, which included a victory over a former white world heavyweight champion, Bob Fitzsimmons. Johnson was relentlessly pursuing the current world heavyweight champion who had succeeded Jeffries, Tommy Burns, by following him around the world.

In the process, Johnson drew enough publicity and attention to his challenge that Burns eventually agreed to a fight on December 26, 1908. Even though Burns was a 3-to-2 favorite, Johnson definitively beat him to win the heavyweight champion title; but the press immediately called for the undefeated Jeffries to return and defend his race as “the Great White Hope.” Once Jeffries acquiesced, the fight was opened up for promoters to bid on, the resulting arrangement becoming the largest legitimate business deal consummated by an African-American up to that time. Riding on this fight was the ubiquitous belief at the time that white people were athletically superior, something that Jeffries and Johnson both knew as they arrived in Reno, Nevada for the July 4, 1910 fight. In fifteen rounds Johnson decimated the Great White Hope, becoming the undisputed heavyweight champion and proving the ability of black athleticism to match and even exceed that of whites.

In the days following the fight, white people around the country murdered thirteen blacks and injured many more in acts of revenge over Jeffries’ loss. Johnson was eventually charged and convicted of trumped of crimes, mainly in relation to his affinity for white female companions. Evading his sentence and fleeing the country, his career was severely damaged and eventually ended with him throwing a fight to Jess Willard in 1915. Despite this, his career paved the way for black athletes to compete in a range of sports and remains a touchstone to overcoming racial barriers.

Photo courtesy of Hard Road to Glory, the Nevada Historical Society