Remembering Arthur Ashe on His Birthday

What makes a legend?

This question has always been the subject of great debate. Some individuals maintain that it is what one accomplishes throughout his or her lifetime that warrants a place in history. Others understand the title as the way in which the person is remembered by those still living. While the word’s definition may be consistently questioned, many would agree that Arthur Ashe is a contender for this title.

A true champion on and off the tennis court, Ashe strived to improve not only the lives of his friends and family but also those of everyone around him. His accomplishments have done much to improve race relations around the world, including in his hometown of Richmond, Virginia. Furthermore, his endeavors promoting education, active citizenship and health and wellness continue to impact the lives of children and youth throughout the country. To this day, his legacy as a tennis player and activist lives on through his immediate family and numerous organizations that strive to build on Arthur’s vision.

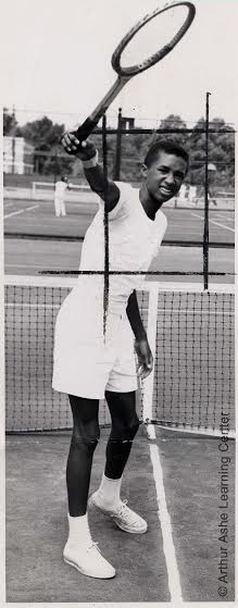

Ashe was born in 1943 in Richmond, Virginia to parents Arthur, Sr. and Mattie Cunningham Ashe. He began playing tennis at the age of seven and went on to earn a full scholarship to the University of California, Los Angeles. During this time, he also became the first African-American player to participate in the U.S. Davis Cup Team.

Following college in 1965, Ashe joined the U.S. Army for two years. He continued to play tennis at an amateur level while being stationed at West Point, winning the inaugural U.S. Open in 1968 and eventually became a full time professional following his service. He continued to travel the world and participate in tournaments, winning the Australian Open and Wimbledon in 1970 and 1975, respectively. He also began his role as an activist after South Africa denied him visa to participate in the South African Open. As a response, he campaigned for their exclusion from the International Lawn Tennis Association.

After undergoing quadruple-bypass surgery in 1979, Ashe eventually decided to retire from professional tennis but continued to work full-time on projects such as writing for ABC Sports, captaining the U.S. Davis Cup team and continuing his activism against the South African Apartheid regime. In addition, he authored a number of books, notably A Hard Road to Glory Volumes I-III: A History of the African-American Athlete.

Following a second bypass surgery and a subsequent blood transfusion, it was discovered that Ashe had contracted human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV. Despite his attempt to maintain privacy, this information was eventually leaked to the press, forcing him to reveal his diagnosis in a press conference April 8, 1992. This did not prompt Ashe to slow down by any means: he continued his activism efforts and spoke before the U.N. General Assembly on World AIDS Day, urging delegates to increase funding for disease research. That same year, he was named Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year for his “embodiment of the spirit of sportsmanship and achievement.”

Arthur Ashe died of AIDS-related pneumonia in New York at the age of 49. In memory of his tennis and activism, the Arthur Ashe statue was erected on Monument Avenue in his hometown of Richmond. The statue depicts Ashe carrying a stack of books in one hand and a tennis racquet in the other, symbolizing his love of both knowledge and tennis.

Ashe once said, “True heroism is remarkably sober, very undramatic. It is not the urge to surpass all others at whatever cost, but the urge to serve others at whatever cost.” It is this attitude of humility and giving, of activism throughout his life and the continued efforts of the organizations he founded that truly classify Arthur Ashe as a legend.

This question has always been the subject of great debate. Some individuals maintain that it is what one accomplishes throughout his or her lifetime that warrants a place in history. Others understand the title as the way in which the person is remembered by those still living. While the word’s definition may be consistently questioned, many would agree that Arthur Ashe is a contender for this title.

A true champion on and off the tennis court, Ashe strived to improve not only the lives of his friends and family but also those of everyone around him. His accomplishments have done much to improve race relations around the world, including in his hometown of Richmond, Virginia. Furthermore, his endeavors promoting education, active citizenship and health and wellness continue to impact the lives of children and youth throughout the country. To this day, his legacy as a tennis player and activist lives on through his immediate family and numerous organizations that strive to build on Arthur’s vision.

Ashe was born in 1943 in Richmond, Virginia to parents Arthur, Sr. and Mattie Cunningham Ashe. He began playing tennis at the age of seven and went on to earn a full scholarship to the University of California, Los Angeles. During this time, he also became the first African-American player to participate in the U.S. Davis Cup Team.

Following college in 1965, Ashe joined the U.S. Army for two years. He continued to play tennis at an amateur level while being stationed at West Point, winning the inaugural U.S. Open in 1968 and eventually became a full time professional following his service. He continued to travel the world and participate in tournaments, winning the Australian Open and Wimbledon in 1970 and 1975, respectively. He also began his role as an activist after South Africa denied him visa to participate in the South African Open. As a response, he campaigned for their exclusion from the International Lawn Tennis Association.

After undergoing quadruple-bypass surgery in 1979, Ashe eventually decided to retire from professional tennis but continued to work full-time on projects such as writing for ABC Sports, captaining the U.S. Davis Cup team and continuing his activism against the South African Apartheid regime. In addition, he authored a number of books, notably A Hard Road to Glory Volumes I-III: A History of the African-American Athlete.

Following a second bypass surgery and a subsequent blood transfusion, it was discovered that Ashe had contracted human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV. Despite his attempt to maintain privacy, this information was eventually leaked to the press, forcing him to reveal his diagnosis in a press conference April 8, 1992. This did not prompt Ashe to slow down by any means: he continued his activism efforts and spoke before the U.N. General Assembly on World AIDS Day, urging delegates to increase funding for disease research. That same year, he was named Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year for his “embodiment of the spirit of sportsmanship and achievement.”

Arthur Ashe died of AIDS-related pneumonia in New York at the age of 49. In memory of his tennis and activism, the Arthur Ashe statue was erected on Monument Avenue in his hometown of Richmond. The statue depicts Ashe carrying a stack of books in one hand and a tennis racquet in the other, symbolizing his love of both knowledge and tennis.

Ashe once said, “True heroism is remarkably sober, very undramatic. It is not the urge to surpass all others at whatever cost, but the urge to serve others at whatever cost.” It is this attitude of humility and giving, of activism throughout his life and the continued efforts of the organizations he founded that truly classify Arthur Ashe as a legend.