Trying to Grapple with the Big Problem: The Writings of Richard Wright

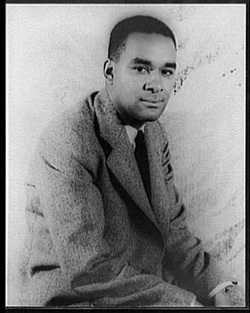

Born September 4, 1908 in Roxie, Mississippi, he spent his childhood in Jackson, MS and Memphis, TN. From a young age he distinguished himself, becoming class valedictorian of his junior high and publishing his first short story at age 16, although he had to drop out of high school after 9th grade to earn money toward family expenses. In 1927 he moved to Chicago but his upbringing in the Jim Crow South would prove a tremendous influence on his beliefs, work and politics.

In the Midwest, he found work as a postal worker and spent much of his free time devoted to books and reading. However, he was not unaffected by the Depression, losing his job in 1931. After that period, his politics shifted toward Communism, especially as a result of his regular attendance of John Reed Club meetings, a national organization affiliated with the Communist Party USA to bring together leftist and Marxist writers, intellectuals, artists, journalists and more. The John Reed Club proved a vehicle for him to increase his literary contacts. Furthermore, in consideration of the tremendous economic downturn across the country and the color blind ideology espoused by leftists and Communists, the Club must have been a comforting association when compared to his experiences of racism and stratified society in America.

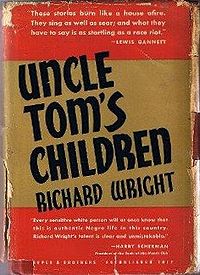

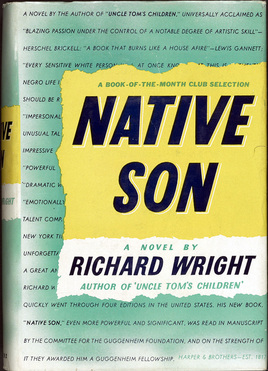

He later joined the Communist party and enjoyed significant success writing poems and short stories for the New Masses and other left-wing publications, eventually becoming an editor of the magazine Left Front. In 1937, after Left Front was shut down, he moved to New York where his Communist connections helped situate him. He became the Harlem editor of the Daily Worker and won a first prize in a contest held by Story magazine with “Fire and Cloud” while also working with the Federal Writers’ Project. Shortly thereafter, he gained significant attention for his short story collection Uncle Tom’s Children. In addition to significant sales and the book being well received, it also earned him a Guggenheim Fellowship, which funded his work writing Native Son, which was published in 1940.

In 1945 he published Black Boy, a semi-autobiographical work chronicling his upbringing in the South through his move to Chicago. Originally titled American Hunger, it contained two parts: the first about his childhood in the South called “Southern Night” and the second about his experiences in Chicago called “The Horror and the Glory.” However, the book was ultimately published without the second part and was renamed Black Boy. It sold over 500,000 copies in its first two editions, an unqualified success.

Throughout the 1940s Wright spent consistently more and more time in Mexico. In 1946 he emigrated to Paris due to his frustrations with the endemic racism in America as well as fear of surveillance (the CIA and FBI began monitoring him in 1943), and eventually became a French citizen. In The Unfinished Quest of Richard Wright, he described the move as “more than a geographical change…I was trying to grapple with the big problem—the problem and meaning of Western civilization as a whole and the relation of Negroes and other minority groups to it” (Michel Fabre, p. 366). His exile in France, rather than ending the “striving for acceptance” in American society as described by Ashe, instead enlarges it: Wright searched not only for the role of the Negro in American society but rather in the entirety of Western civilization.

He was welcomed into Parisian literary society, befriending existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, as well as expatriate Americans Chester Himes and James Baldwin. He continued to write, publishing The Outsider in 1953 and Savage Holiday in 1954, and traveled extensively throughout Europe, Asia and Africa, translating many of his experiences into nonfiction works. These journeys also afforded him the chance at personal observation of the colonial powers, colonies and the post-colonial state, as a way to explore “the big problem.”

Reliant on an American passport for travel purposes, he developed a fraught relationship with the US and its government entities. He reported to the State Department, both naming Communists he had associated with who were being prosecuted and discussing the Gold Coast’s development plans (modern day Ghana), after visiting and conversing with its leaders. However, he also declined to participate in the Congress for Cultural Freedom, despite financial and other incentives, suspecting that it was connected with the CIA.

He continued to publish work until his death in 1960 from a heart attack.

Native Son, and to a lesser extent Black Boy, would remain his most important works that changed ideas and attitudes. Both have been credited with influencing existentialist philosophy and portraying the search for self-actualization. While criticized for depicting a stereotypical violent black man in Native Son, Wright also presented the systemic inevitability of violence starting from a young age when circumscribed opportunities are combined with instruction toward conforming to anticipated outcomes. Even decades after Jim Crow this idea and problem persists in America for many ethnic, socioeconomic, and other groups, waiting to be adequately addressed in greater society.

|

Selected works by Richard Wright:

|