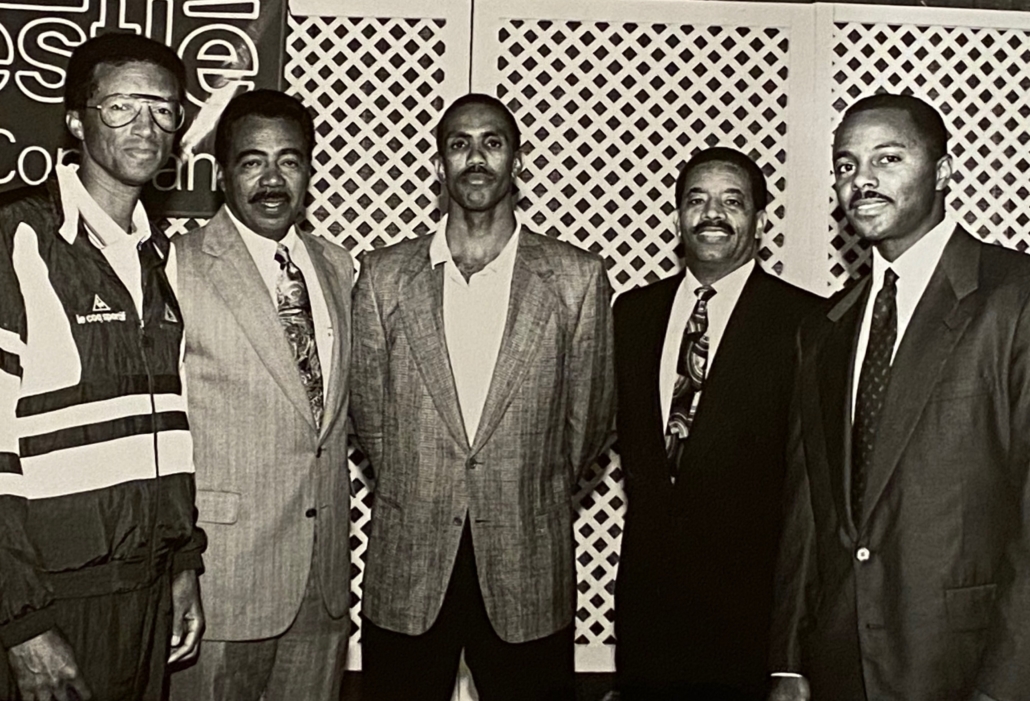

Arthur Ashe, Bob Davis, Ken Bentley, Eugene Boykins, former Nestle executive and UCLA alum; and Kevin Dowdell, 1992. Photo courtesy of Ken Bentley

“We have taken kids and sold them on bouncing a ball and running with a football and that being able to do certain things athletically was going to be an end in itself. We cannot afford to do that to another generation.”

Arthur Ashe, Days of Grace: A Memoir

Throughout his life, Arthur Ashe cultivated promising young tennis talent while encouraging athletic ability as a means to greater impact rather than an end goal itself. As a mentor, Ashe guided and supported several aspiring players, particularly young players of color. One such player was Yannick Noah, who Ashe discovered while traveling in Cameroon. After Ashe vouched for his potential to the French Tennis Federation, this ultimately set Noah on the path to winning the French Open in 1983. Ashe’s other mentees included fellow proteges of Dr. Robert Walter Johnson, like Juan Farrow and Luis Glass. Glass, in particular, Ashe took under his wing after he accepted a tennis scholarship to join Ashe and the Bruins at UCLA.

Ken Bentley was another such player that Ashe mentored. After his historic U.S. Open win in 1968, Ashe made a point of meeting Bentley at the Pacific Southwest Tennis Tournament after seeing his mother waiting in her car outside the event. Bentley was still in high school at the time, and while Ashe took an interest in his tennis, he was also candid about broadening his focus beyond tennis. Through his relationship with Bentley and other young players, Ashe demonstrated that cultivating the next generation of Black tennis talent was not the singular objective of his mentorship. Instead, he emphasized using tennis to open doors to other possibilities, especially within academics and future career pursuits.

This philosophy of using sports to achieve a higher purpose is one that Ashe embodied through his own life, and it also seemed to live on through those he mentored. Both Farrow and Glass became coaches within the National Junior Tennis League, which Ashe co-founded in 1969 to increase opportunities for young people from diverse and underserved backgrounds to learn tennis. Similarly, Yannick Noah became an influential activist for making tennis more accessible to underprivileged youth and increasing AIDS awareness.

For Bentley, the legacy of his relationship with Ashe is also evident throughout his life. Bentley secured the first corporate donation for Ashe’s Safe Passage Foundation, which sought to support young Black people from impoverished backgrounds to make a safe transition from youth to adulthood. Moreover, when Bentley founded his own organization in 2008, the Advocates Pro Golf Association, he promoted a similar philosophy of broadening access to a traditionally restrictive sport, while getting young people to expand their future horizons. As Bentley’s story illustrates, for many who were touted as the “next Arthur Ashe,” following in his footsteps was less defined by what they achieved on the courts and more by who they were and what they did when they stepped off. Listen in as Bentley describes his first time meeting Ashe.

If you know of anyone who has a personal connection to Arthur Ashe and would like to be interviewed, please email us at: Ashehistoryproject@college.ucla.edu

The full interviews will be available online on the Center For Oral History Research site soon. We will announce when they are available. For more information on The Arthur Ashe Legacy Fund and The Center For Oral History Research, please visit their websites at:

Chinyere Nwonye

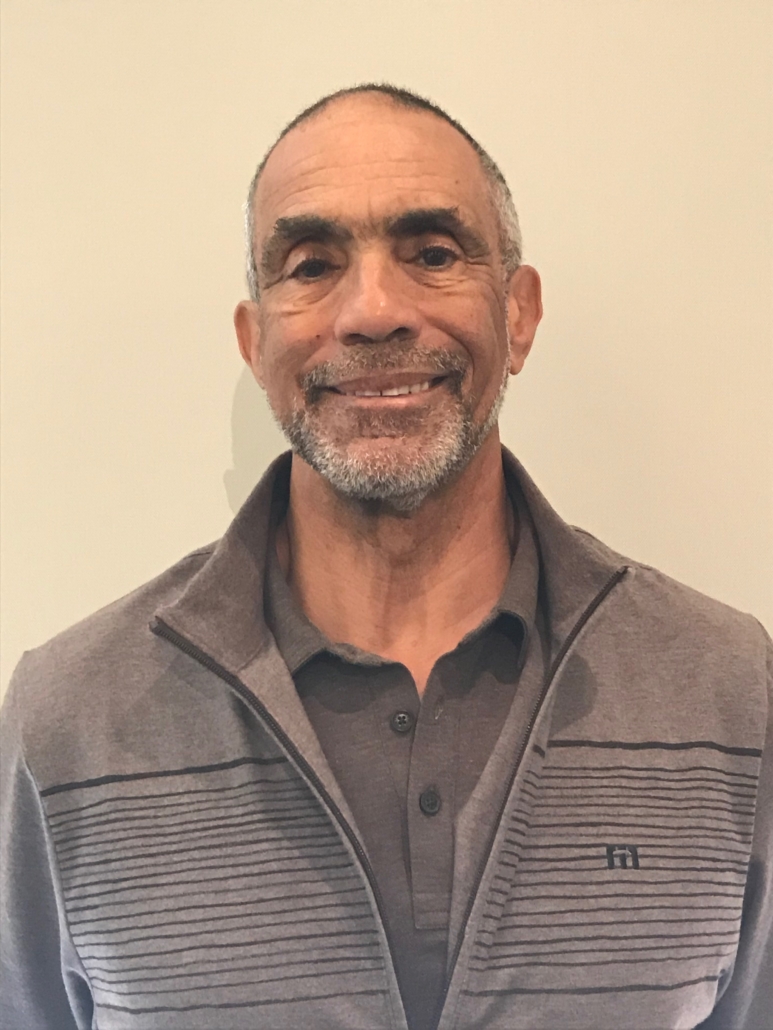

Ken Bentley