Chronicle of Reconstruction: The Story of John R. Lynch

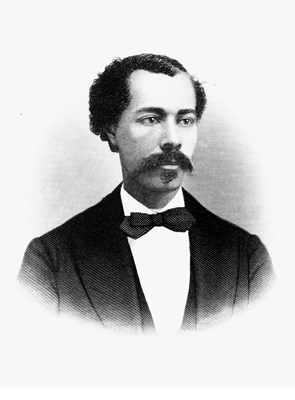

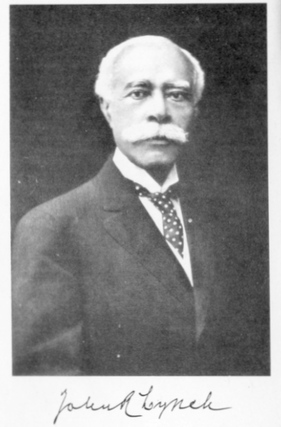

The photo from Lynch’s 1913 book

The photo from Lynch’s 1913 book

John Roy Lynch was an American politician, writer, attorney, and military officer, who was born into slavery, gained freedom in 1863 and was subsequently elected to both the Mississippi House of Representatives and the U.S. House of Representatives.

Lynch was born in 1847 on the Tacony Plantation near Vidalia, Concordia Parish, Louisiana to Catherine White, a slave of mixed race, and Patrick Lynch, a young, white immigrant from Dublin, Ireland. His parents, who were in love but were forbidden from marriage due to state law, approached the plantation owner and purchased his freedom of his family; however, when the plantation hired a new manager, Lynch could not afford to pay the bond required for each person. An additional plan was created to eventually secure Catherine and her children’s freedom, but Patrick Lynch died before those plans could be finalized.

A friend of Lynch Sr.’s, William G. Deal, was to take the title of the family members, as a method of protection. However, Deal sold the members of the White/Lynch family to a planter in Mississippi. Upon hearing of Catherine’s situation, the planter agreed to allow her to remain connected to the Deal household, as well as save a portion of her income. John Lynch was eventually sent to field labor on the plantation, but a Union Army victory and President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation secured his freedom at the age of sixteen. Lynch began work for a photographer in Natchez, Mississippi following the end of the Civil War, eventually taking over management of the operation. He also expressed a desire to further his education, briefly attending a night school taught by Northerners and eavesdropping on lessons at a nearby white school.

Lynch became known within the community for his leadership abilities and, by the age of 20, became increasingly active within the Republican Party. Although he was far too young to participate as a delegate, he was able to attend the 1867 Constitutional Convention purely in a spectator role. Two years later, he was appointed as Justice of the Peace by the then-military governor, Adelbert Ames, and soon after was elected to the Mississippi State House of Representatives. At only 24 years old he was chosen as speaker, becoming the first African-American to hold that position in the State. He held that position until 1873.

During his last term in the state House at the age of 26, Lynch was elected to Congress from Mississippi’s 6th congressional district becoming the House of Representatives youngest member. While there, he introduced many bills and argued on behalf of the rights of African-Americans. He is arguably best known for his involvement in and support of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, also known as the Enforcement Act, which prohibited discrimination in public accommodations and on public transportation and also protected the right to serve on juries. Lynch, alongside six other African-American congressmen, testified about his knowledge and personal experience of discrimination occurring in the Mississippi area. The act passed the Congress and was signed into law on March 1, 1975; unfortunately, eight years later a Supreme Court decision found it unconstitutional and hollowed out the provisions, paving the way for the policy of “separate but equal.”

1875 was a contentious election cycle in Mississippi, as the Democrats had implemented a statewide plan to suppress black voting through violence and economic coercion. Lynch narrowly kept his seat—the only black representative from the state to do so. Once back in session, the Democratic Party had retaken the House. He spent much of his term bringing attention to the actions of the white supremacist paramilitary groups connected to the Democratic Party, such as the Red Shirts and White League. Both of these terror groups were comprised mostly of Confederate veterans who operated openly and were committed to restoring the dominance of the Democratic Party through voter suppression, intimidation and violence. The White League specifically was involved with multiple murders, including that of schoolteacher Julia Hayden and the Coushatta Massacre, where six Republicans were assassinated along with five to 20 freedmen.

In 1876, Mississippi’s Democratic Party protested Lynch’s third-term election—the result of several years worth of fraud and associated violence. Eventually, the Elections Committee, which was majority Democrat, ruled against Lynch, removing him from office and effectively ending Reconstruction in the state. Lynch ran again in 1880, and after contesting a Democratic victory, was awarded the seat by Congress in 1882. During this session he worked to advance the economic interests of Mississippi, seeking monies for projects ranging from an orphanage to coastline improvements to a National Board of Health to address health emergencies. However, the next election was already almost upon him, thus he mounted a severely reduced campaign and lost his seat in 1882.

In 1884, Lynch became the first African-American to chair a National Convention after future president Theodore Roosevelt made Lynch the Temporary Chairman of the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Illinois. He also delivered a keynote address during the conference, the only African-American to do so until 1968.

Later in his political career, Lynch returned to Mississippi to study law, passing the state bar in 1896 before relocating to Washington D.C. and opening a practice. After a year he was appointed a major in the Army by President William McKinley, helping the Spanish-American War effort. After spending 13 years in the Army, he retired in 1911 and moved to Chicago, where he opened up another law practice. He was one of the many blacks who relocated from Southern States to Central, Northern and Western states as part of the Great Migration. He became involved in real estate there, capitalizing on the tremendous demographic shift.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the meaning and representation of the Civil War and Reconstruction was in flux. Many Southern authors and historians sympathized with the white former slaveholders’ position, disparaging the post-war Republican period and downplaying or ignoring the accomplishments and agency of blacks. This became a dominant narrative about that period up through the 1930s, reinforcing and validating the Jim Crow system by extension. Lynch sought to correct this by publishing The Facts of Reconstruction in 1913, which provides evidence of black achievements and contributions and recalls his experiences. It was well-received by several American scholars such as W.E.B DuBois and became an important primary text in American history. He authored multiple books about this issue, in addition to a memoir that was published posthumously in 1970. He passed away November 2, 1939 in Chicago.

John R. Lynch’s career is truly inspiring: from political battles to military service to wor

ks of scholarship that stand as a testament to the African-American experience at the turn of the century. His foray into the political realm at a young age, followed by his incredible rise to top government positions as a black man, set an inspirational precedent for all future generations of Americans.

Read the entirety of Facts of Reconstruction online through the Gutenberg Project.

Lynch was born in 1847 on the Tacony Plantation near Vidalia, Concordia Parish, Louisiana to Catherine White, a slave of mixed race, and Patrick Lynch, a young, white immigrant from Dublin, Ireland. His parents, who were in love but were forbidden from marriage due to state law, approached the plantation owner and purchased his freedom of his family; however, when the plantation hired a new manager, Lynch could not afford to pay the bond required for each person. An additional plan was created to eventually secure Catherine and her children’s freedom, but Patrick Lynch died before those plans could be finalized.

A friend of Lynch Sr.’s, William G. Deal, was to take the title of the family members, as a method of protection. However, Deal sold the members of the White/Lynch family to a planter in Mississippi. Upon hearing of Catherine’s situation, the planter agreed to allow her to remain connected to the Deal household, as well as save a portion of her income. John Lynch was eventually sent to field labor on the plantation, but a Union Army victory and President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation secured his freedom at the age of sixteen. Lynch began work for a photographer in Natchez, Mississippi following the end of the Civil War, eventually taking over management of the operation. He also expressed a desire to further his education, briefly attending a night school taught by Northerners and eavesdropping on lessons at a nearby white school.

Lynch became known within the community for his leadership abilities and, by the age of 20, became increasingly active within the Republican Party. Although he was far too young to participate as a delegate, he was able to attend the 1867 Constitutional Convention purely in a spectator role. Two years later, he was appointed as Justice of the Peace by the then-military governor, Adelbert Ames, and soon after was elected to the Mississippi State House of Representatives. At only 24 years old he was chosen as speaker, becoming the first African-American to hold that position in the State. He held that position until 1873.

During his last term in the state House at the age of 26, Lynch was elected to Congress from Mississippi’s 6th congressional district becoming the House of Representatives youngest member. While there, he introduced many bills and argued on behalf of the rights of African-Americans. He is arguably best known for his involvement in and support of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, also known as the Enforcement Act, which prohibited discrimination in public accommodations and on public transportation and also protected the right to serve on juries. Lynch, alongside six other African-American congressmen, testified about his knowledge and personal experience of discrimination occurring in the Mississippi area. The act passed the Congress and was signed into law on March 1, 1975; unfortunately, eight years later a Supreme Court decision found it unconstitutional and hollowed out the provisions, paving the way for the policy of “separate but equal.”

1875 was a contentious election cycle in Mississippi, as the Democrats had implemented a statewide plan to suppress black voting through violence and economic coercion. Lynch narrowly kept his seat—the only black representative from the state to do so. Once back in session, the Democratic Party had retaken the House. He spent much of his term bringing attention to the actions of the white supremacist paramilitary groups connected to the Democratic Party, such as the Red Shirts and White League. Both of these terror groups were comprised mostly of Confederate veterans who operated openly and were committed to restoring the dominance of the Democratic Party through voter suppression, intimidation and violence. The White League specifically was involved with multiple murders, including that of schoolteacher Julia Hayden and the Coushatta Massacre, where six Republicans were assassinated along with five to 20 freedmen.

In 1876, Mississippi’s Democratic Party protested Lynch’s third-term election—the result of several years worth of fraud and associated violence. Eventually, the Elections Committee, which was majority Democrat, ruled against Lynch, removing him from office and effectively ending Reconstruction in the state. Lynch ran again in 1880, and after contesting a Democratic victory, was awarded the seat by Congress in 1882. During this session he worked to advance the economic interests of Mississippi, seeking monies for projects ranging from an orphanage to coastline improvements to a National Board of Health to address health emergencies. However, the next election was already almost upon him, thus he mounted a severely reduced campaign and lost his seat in 1882.

In 1884, Lynch became the first African-American to chair a National Convention after future president Theodore Roosevelt made Lynch the Temporary Chairman of the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Illinois. He also delivered a keynote address during the conference, the only African-American to do so until 1968.

Later in his political career, Lynch returned to Mississippi to study law, passing the state bar in 1896 before relocating to Washington D.C. and opening a practice. After a year he was appointed a major in the Army by President William McKinley, helping the Spanish-American War effort. After spending 13 years in the Army, he retired in 1911 and moved to Chicago, where he opened up another law practice. He was one of the many blacks who relocated from Southern States to Central, Northern and Western states as part of the Great Migration. He became involved in real estate there, capitalizing on the tremendous demographic shift.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the meaning and representation of the Civil War and Reconstruction was in flux. Many Southern authors and historians sympathized with the white former slaveholders’ position, disparaging the post-war Republican period and downplaying or ignoring the accomplishments and agency of blacks. This became a dominant narrative about that period up through the 1930s, reinforcing and validating the Jim Crow system by extension. Lynch sought to correct this by publishing The Facts of Reconstruction in 1913, which provides evidence of black achievements and contributions and recalls his experiences. It was well-received by several American scholars such as W.E.B DuBois and became an important primary text in American history. He authored multiple books about this issue, in addition to a memoir that was published posthumously in 1970. He passed away November 2, 1939 in Chicago.

John R. Lynch’s career is truly inspiring: from political battles to military service to wor

ks of scholarship that stand as a testament to the African-American experience at the turn of the century. His foray into the political realm at a young age, followed by his incredible rise to top government positions as a black man, set an inspirational precedent for all future generations of Americans.

Read the entirety of Facts of Reconstruction online through the Gutenberg Project.