The First African-American Congressman: Hiram Rhodes Revels

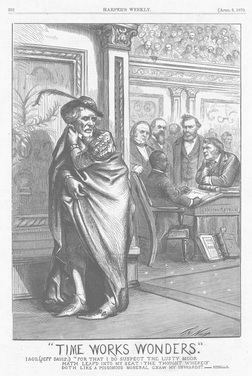

In this political cartoon, Revels (seated) replaces Jefferson Davis (left in costume as Iago from Shakespeare’s Othello) in the US Senate. Harper’s Weekly Feb. 19, 1870.

In this political cartoon, Revels (seated) replaces Jefferson Davis (left in costume as Iago from Shakespeare’s Othello) in the US Senate. Harper’s Weekly Feb. 19, 1870.

For this 2016 election year, to celebrate Black History Month the Arthur Ashe Learning Center will profile various African-American elected officials throughout history. Starting back in the Reconstruction period, today we take a look at Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first African-American elected to serve in the United States Congress.

Hiram Rhodes Revels was born on September 27, 1827 in Fayetteville, North Carolina, to free, colored parents of African American and Native American ancestry. In 1842, he relocated to Lincolnton, NC and took up work as a barber before later leaving the South to enroll at Beech Grove Seminary, a Quaker institution located in Liberty, Indiana. Revels also attended Darke County Seminary for Negroes in Ohio in 1845 and eventually became an ordained minister in the predominantly black African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.

Revels traveled throughout much of the Midwest as a preacher and religious teacher for both free and enslaved African Americans. At one point he led an AME Church in St. Louis, Missouri, despite the fact that free blacks were forbidden from living within the state. He was arrested a year later in 1854 for preaching. After that episode, he briefly moved to Baltimore before re-enrolling in school, attending Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois with a concentration in religion. During the Civil War, he joined the Union Army served as a chaplain from 1863-65, helping to recruit and organize black work battalions for the Union Army. Alongside this position, Revels simultaneously opened a black high school in St. Louis and founded several churches throughout the South. Eventually he left the AME denomination and switched to Methodist Episcopal church.

After the war, he continued to preach in various locations before moving to Natchez, Mississippi in 1866. His work in politics began in 1869, when Revels ran as a Republican and was elected by an 81-15 vote to the Mississippi State Senate to represent Adams County. Revels was seen as an ideal candidate for the position, given his position as a well-educated, African-American man. He immediately stood out when he led the opening prayer on the on the first day of the legislative session. At the time, Mississippi and many other Southern states did not have representation in the U.S. senate and house because their elected officials had resigned at the onset of the Civil War and were never replaced. Thus, the state senate was tasked with filling these federal vacancies for the remainder of the current terms. Revels was overwhelmingly voted to fill one of these seats on January 20, 1880.

However, his arrival in the nation’s capital was met with great opposition from southern Democrats, who tried multiple stratagems to keep him from being seated. They claimed Mississippi was under military rule and did not have a civil government in place, which would invalidate his election. They also claimed that he did not meet the qualifications to be a senator, basing their argument upon the 1857 Dred Scott Supreme Court decision. That decision ruled that no individual of African ancestry was or could be considered a citizen of the United States. After the Civil War, the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, granted citizenship to all individuals “born or naturalized in the United States,” but it was ratified in 1868 – thus, the Democrats argued that Revels had only been a citizen since the amendment and did not fulfill the nine years citizenship clause for becoming a senator.

Supporters of Revels, however, claimed that the Civil War, as well as those amendments created during the Reconstruction period, had overturned the Dred Scott decision, among other oppressive pieces of legislature against African-Americans. Therefore, it would be unconstitutional to deny Revels a seat in the Senate based upon outdated laws. On February 25, 1870, Revels became the first African American to be seated in the U.S. Senate and Congress, winning a 48-8 party-line vote in his favor.

During his time as senator, Revels introduced three bills, one of which was successfully passed. An open advocate of amnesty for ex-Confederate soldiers contingent upon a declaration of loyalty, his bill was a petition to eradicate the political and civil disabilities of ex-Confederate officers and officials, restoring their full citizenship. For this, Revels received some backlash from the black community but also secured a reputation as a moderate. He also served the Committee of Education and Labor and Committee on the District of Columbia, where he focused on several additional Reconstruction issues. He successfully helped black mechanics be admitted to work at the U.S. Navy Yard in Baltimore and fought against an amendment to continue segregated schooling in the District of Columbia. Revels left his position in March of 1871 when the term expired.

Revels returned to Mississippi following the end of his term, where he became involved in several projects. He was a co-founder of Alcorn University in 1872, which was the first land-grant school for blacks, serving as its first president until his appointment as Mississippi’s Secretary of State. He eventually returned to the presidency, but soon after resigned due to poor health and financial issues within the institution. In his later years, he moved to Holly Springs, Mississippi with his family, where he continued his religious teachings and ministry until his death on January 16, 1901.

While controversial in his time, Revels’ actions set an important precedent in the history of African-Americans within the United States. He was unafraid to take positions that his black constituents or peers might find unappealing, taking his duty to represent ALL of his fellow citizens very seriously. Furthermore, there is a certain beauty and irony in his becoming the first African-American congressman: elected Senator from the same state as Jefferson Davis who had left the senate, becoming president of the Confederacy. Although Revels’ political career was short, he provided a trailblazing path for the 21 African-Americans who would be seated in the U.S. Congress following him during the period of Reconstruction.

Hiram Rhodes Revels was born on September 27, 1827 in Fayetteville, North Carolina, to free, colored parents of African American and Native American ancestry. In 1842, he relocated to Lincolnton, NC and took up work as a barber before later leaving the South to enroll at Beech Grove Seminary, a Quaker institution located in Liberty, Indiana. Revels also attended Darke County Seminary for Negroes in Ohio in 1845 and eventually became an ordained minister in the predominantly black African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.

Revels traveled throughout much of the Midwest as a preacher and religious teacher for both free and enslaved African Americans. At one point he led an AME Church in St. Louis, Missouri, despite the fact that free blacks were forbidden from living within the state. He was arrested a year later in 1854 for preaching. After that episode, he briefly moved to Baltimore before re-enrolling in school, attending Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois with a concentration in religion. During the Civil War, he joined the Union Army served as a chaplain from 1863-65, helping to recruit and organize black work battalions for the Union Army. Alongside this position, Revels simultaneously opened a black high school in St. Louis and founded several churches throughout the South. Eventually he left the AME denomination and switched to Methodist Episcopal church.

After the war, he continued to preach in various locations before moving to Natchez, Mississippi in 1866. His work in politics began in 1869, when Revels ran as a Republican and was elected by an 81-15 vote to the Mississippi State Senate to represent Adams County. Revels was seen as an ideal candidate for the position, given his position as a well-educated, African-American man. He immediately stood out when he led the opening prayer on the on the first day of the legislative session. At the time, Mississippi and many other Southern states did not have representation in the U.S. senate and house because their elected officials had resigned at the onset of the Civil War and were never replaced. Thus, the state senate was tasked with filling these federal vacancies for the remainder of the current terms. Revels was overwhelmingly voted to fill one of these seats on January 20, 1880.

However, his arrival in the nation’s capital was met with great opposition from southern Democrats, who tried multiple stratagems to keep him from being seated. They claimed Mississippi was under military rule and did not have a civil government in place, which would invalidate his election. They also claimed that he did not meet the qualifications to be a senator, basing their argument upon the 1857 Dred Scott Supreme Court decision. That decision ruled that no individual of African ancestry was or could be considered a citizen of the United States. After the Civil War, the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, granted citizenship to all individuals “born or naturalized in the United States,” but it was ratified in 1868 – thus, the Democrats argued that Revels had only been a citizen since the amendment and did not fulfill the nine years citizenship clause for becoming a senator.

Supporters of Revels, however, claimed that the Civil War, as well as those amendments created during the Reconstruction period, had overturned the Dred Scott decision, among other oppressive pieces of legislature against African-Americans. Therefore, it would be unconstitutional to deny Revels a seat in the Senate based upon outdated laws. On February 25, 1870, Revels became the first African American to be seated in the U.S. Senate and Congress, winning a 48-8 party-line vote in his favor.

During his time as senator, Revels introduced three bills, one of which was successfully passed. An open advocate of amnesty for ex-Confederate soldiers contingent upon a declaration of loyalty, his bill was a petition to eradicate the political and civil disabilities of ex-Confederate officers and officials, restoring their full citizenship. For this, Revels received some backlash from the black community but also secured a reputation as a moderate. He also served the Committee of Education and Labor and Committee on the District of Columbia, where he focused on several additional Reconstruction issues. He successfully helped black mechanics be admitted to work at the U.S. Navy Yard in Baltimore and fought against an amendment to continue segregated schooling in the District of Columbia. Revels left his position in March of 1871 when the term expired.

Revels returned to Mississippi following the end of his term, where he became involved in several projects. He was a co-founder of Alcorn University in 1872, which was the first land-grant school for blacks, serving as its first president until his appointment as Mississippi’s Secretary of State. He eventually returned to the presidency, but soon after resigned due to poor health and financial issues within the institution. In his later years, he moved to Holly Springs, Mississippi with his family, where he continued his religious teachings and ministry until his death on January 16, 1901.

While controversial in his time, Revels’ actions set an important precedent in the history of African-Americans within the United States. He was unafraid to take positions that his black constituents or peers might find unappealing, taking his duty to represent ALL of his fellow citizens very seriously. Furthermore, there is a certain beauty and irony in his becoming the first African-American congressman: elected Senator from the same state as Jefferson Davis who had left the senate, becoming president of the Confederacy. Although Revels’ political career was short, he provided a trailblazing path for the 21 African-Americans who would be seated in the U.S. Congress following him during the period of Reconstruction.