The Tallest Tree in the Forest

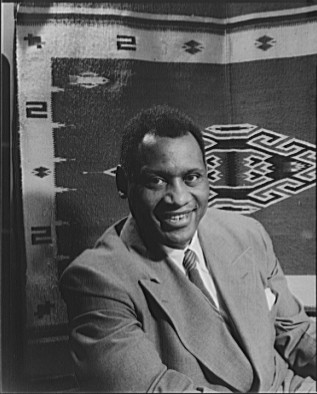

Photo courtesy of Hard Road to Glory, Rutgers University

Photo courtesy of Hard Road to Glory, Rutgers University

Paul Robeson was born in 1898: his father had escaped slavery and put himself through school and his mother came from a distinguished multiracial Quaker family in Philadelphia. Robeson grew up in a hardworking household with charitable values. He excelled academically and was awarded a four-year scholarship to Rutgers University, one of the oldest universities in the United States. Robeson was only the third African American to receive this scholarship. There, Robeson excelled in oratory and debate skills as well as athletics. He was admitted to Phi Beta Kappa and received an unprecedented fifteen varsity letters for various sports. Robeson was also selected for the All-American Football team twice, first in 1917 then in 1918, making Rutgers history as the first athlete there to receive the honor. He went on to become his class valedictorian.

After Rutgers, Robeson attended Columbia Law School, where he subsidized his tuition by playing professional football. He also began acting. After graduation, he had a short stint practicing law before experiencing racism at the firm. Robeson left his job and the field of law forever. Still a skilled orator, he utilized his talents in public speaking and transitioned to acting, becoming a figure in the Harlem Renaissance after positive reviews in the plays The Emperor Jones and All God’s Chillun Got Wings. As Ashe mentioned in his New York Public Library lecture in 1987, African Americans were often denied access in certain occupations, but special acceptances were allotted in the fields of entertainment and sports*. His wife, Eslanda Goode, was a vigorous proponent of his career, quitting her job to become his agent and negotiating his first film role.

During the same period, he met Lawrence Brown, a renowned pianist, in Harlem and after performing a few impromptu spirituals, they booked a concert which later led to a series of concert tours in America and Europe from 1926 – 1927.

In the 1930s Robeson became an acclaimed entertainer and international star performing in the stage versions of Show Boat and Othello in London and the movies Show Boat and Sanders of the River. During this period, he spent much of his time in London, having purchased a house there and enjoying numerous roles in theater. In 1933 he appeared in the film version of The Emperor Jones, the first film starring an African American. Soon after, he became interested in Africa, his ancestry and anti-Imperialism. He and his wife visited the Soviet Union having been invited by filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein.

This marked the beginning of his political activism. He noted the racism in Nazi Germany during a brief stopover and upon returning to America, became more particular about the roles he chose. He also advocated that black players should be admitted into Major League Baseball and relentlessly pursued civil rights: meeting with President Truman about lynching, asking the public to demand civil rights legislation from Congress and forming the American Crusade Against Lynching organization in 1946. Two years later he campaigned all across the country—including the Jim Crow South—for Henry Wallace’s presidential campaign.

Soon after Robeson spoke at the World Peace Council conference in Paris, 1949 drawing a lot of negative publicity back home. The group, an outgrowth of the Soviet Union’s Communist Party, advocated that the Soviet Union was not aggressive and America was a global imperialist aggressor. Between that and his visiting Moscow again, Robeson found himself shunned and blacklisted in the United States.

Photo courtesy of Wiki Commons

Photo courtesy of Wiki Commons

Despite how popular he had been in entertainment, the media portrayal of his political standings left him discredited in the public eye. This negative depiction and not being able to travel led to the downfall of his career. He published an autobiography called Here I Stand in 1958. That same year, his passport was reinstated after the Supreme Court decision Kent v. Dulles and he undertook a world tour.

Over the course of his life, the stresses of his career, activism and public controversy took its toll and he began to have heart problems in 1959. At around the same time, his wife was found to have terminal cancer. They went on a tour of Australia and New Zealand in late 1960 where he was awakened to the plight of the Aborigines and Maori and spoke up for them and their rights. Soon after that, his health deteriorated further and he suffered bouts of paranoia and depression and attempted suicide.

In 1963 Robeson retired from the public eye and returned to the United States. Although he was courted by the mainstream Civil Rights Movement, nothing came of it because of his Communist sympathies. His wife died in 1965 and he passed away in 1976 at the age of 77 in Philadelphia, PA. Robeson’s professional successes in many fields, his courage in the face of significant opposition, his integrity as an opinionated man who stood up for what he believed in position him as an inspirational and important figure in American history.

Today, people who regard him as a historic icon are working to ensure his story is told. The Tallest Tree in the Forest is a solo play touring the country about Robeson’s life written and starring Daniel Beaty. It will open March 22nd at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York for a weeklong engagement. For more information check out their site: http://www.bam.org/theater/2015/the-tallest-tree-in-the-forest