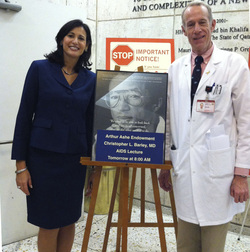

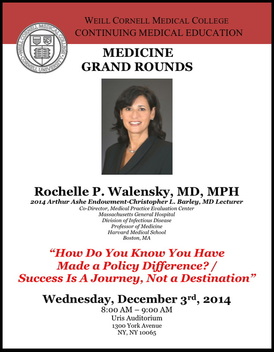

The Journey to Better HIV/AIDS Policy: Arthur Ashe Endowment for the Defeat of AIDS Honors World AIDS Week with Lecture from Dr. Rochelle Walensky

Having this empirical way to evaluate diagnostic screening, treatments, programs and guidelines helps to create more effective policy and focus that policy, and can save more years of people’s lives using the same amount of resources. An interesting question arises, though, when looking at the benchmark dollar amount per QALY used for a treatment to be considered cost-effective in one country versus another. Traditionally, for instance, in the United States, for an intervention to be considered cost-effective, it should cost less than or equal to $50,000 per QALY. However, in a country such as Malawi in Africa, with much less wealth as judged for example by gross national product, that figure drops to $400 per QALY. Since most HIV treatments cost far more than $400 per year, applying traditional measures of cost-effectiveness are not likely relevant in resource-limited countries.

In addition to results of various cost-effectiveness studies involving HIV/AIDS treatment and medications, some other interesting facts that were discussed by Dr. Walensky included:

- In 1989, there was only one FDA-approved antiretroviral drug to treat HIV; in 2014, there are more than 20 approved drugs for HIV infection and more in testing. The expansion of research into these treatments has not only benefited HIV patients, but also led to the development of other antiviral drugs to address other diseases such as infections caused by herpesvirus and hepatitis B and C.

- In 1996, HIV treatment required taking as many as 18-24 pills per day; in 2014, a number of effective treatments require only one pill day.

- Interventions in HIV/AIDS have thus far saved over 3 millions years of life in the United States.

Dr. Walensky introduced a timeline of Arthur Ashe’s experience with HIV/AIDS to illustrate larger issues about the evolution of treatment and policy and the relevance of her own work. One example she talked about was how he learned of his infection through a diagnostic test for HIV infection once he had presented with toxoplasmosis, an infection that most commonly occurs in people with AIDS. However, currently in America, HIV infection is typically detected through screening—people are encouraged to be tested regularly, especially members of high risk populations—and, because of testing for HIV infection, can be found at a less advanced stage which leads to more successful treatment and longer life.

The benefit of routine screening by blood testing versus waiting for symptoms to develop (e.g., toxoplasmosis, reflecting advanced infection (or AIDS)) is a good example of a successful intervention or change in practice. Furthermore, not only does routine screening now extend patients lives, it is also cost-effective –meaning that regular testing saves more money than waiting until a patient is symptomatic or ill to conduct diagnostic tests. Dr. Walensky’s work also examines interventions using cost-effectiveness analysis to look at specific medications, treatment regimens or timing of treatments to see how they compare.