Willard Motley’s Chicago Style

After traveling for a period after he finished school, he returned to Chicago and helped found the Hull-House Magazine in 1939. This was a project of Jane Addam’s Hull House, a settlement house that provided social and educational opportunities to the working class, particularly European immigrants. He wrote articles for the publication using fragmented descriptions to paint a vivid picture of his (and the Hull House) neighborhood, such as “This is the street of noises, of odors, of colors….from Africa to Mexico one block; from Mexico to Italy two blocks; from Italy to Greece three blocks…” (Motley, “Pavement Portraits,” The Hull-House Magazine 1, no. 2 (December 1939) p. 2) The influence of this neighborhood and experience would be reflected later in his novels. In 1940, like many of the African-American authors of this time, he worked for the Works Progress Administration Federal Writers Project. Around this time he also became more politically active, becoming a conscientious objector to the war because of segregation in the U.S. military.

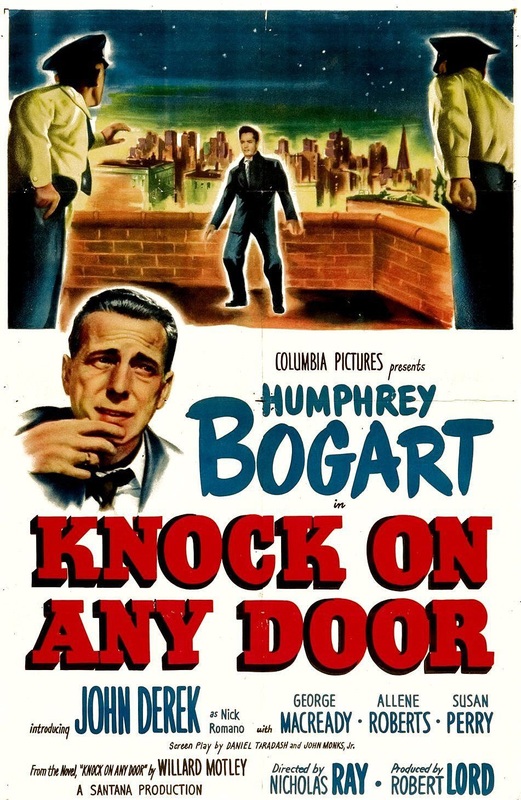

In 1947 he released Knock on Any Door, his first novel and an immediate hit. It sold selling 47,000 copies in the first three weeks and became a 1949 movie starring Humphrey Bogart. The story revolves around a young man, Nick Romano, who starts off as a studious kid but after family misfortune (his father loses his job and they are forced to move to a slum) and misunderstandings (he is punished for a crime he does not commit), eventually kills a cop and is then sentenced to death and executed. Like Wright’s Native Son, his character commits a crime but is also shown to be the victims of the circumstances he is born into, primarily poverty. During the eight years of Nick’s life that the book follows, he is subjected to social, institutional and psychological blows that provide the percussive drum roll of the inexorable march toward his death at 21. Nick famously says, “Live fast, die young and have a good-looking corpse.”

Interestingly, the protagonist is an Italian-American and much of it is set in an Italian immigrant community in Chicago. This is unlike many other black authors of the time who set out to present some aspect of the African-American experience. When criticized about his choice to write about white characters, Motley responded “My race is the human race.” This choice certainly aligns with his earlier pieces, such as the “Pavement Portraits” where he spends much of the article discussing the Mexican community.

|

In 1947, Motley became involved in a campaign to save James Hickman, a man who was charged with murder and faced possible sentencing to execution after shooting and killing his landlord, who was suspected of setting fire to his apartment building, resulting in the deaths of four of Hickman’s children. A large defense campaign was mounted by labor activists, the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party and other liberals in the city who contended that the squalid housing conditions African-Americans were forced into were the real problem (at the time, many real estate companies and property owners refused to rent or sell to blacks, confining them to specific enclaves and ghettos in the city). Motley worked his connections at newspapers and publications to garner the populace’s sympathy for Hickman’s plight. Hickman’s trial ended with a hung jury and the State’s Attorney chose not to continue prosecution due to the public outcry.

|

He died in 1965 in Mexico City. The unfinished Let Noon Be Fair was published posthumously in 1966. As the 2013 Chicago Literary Hall of Fame awards stated, “Motley was criticized in his life for being a black man writing about white characters, a middle-class man writing about the lower class, and a closeted homosexual writing about heterosexual urges. But those more kindly disposed to his work, and there were plenty, admired his grit and heart….Chicago was more complicated than just its racial or sexual tensions, and as a writer his exploration was expansive.”* To this day, Chicago annually holds the Bud Billiken Day Parade, the oldest and largest African American parade in the country, dedicated toward bettering Chicago youth.

Selected works by Willard Motley:

- “Pavement Portraits,” The Hull-House Magazine 1, no. 2 (December 1939) p. 2-6.

- Knock on Any Door (New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1947).

- We Fished All Night (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1951).

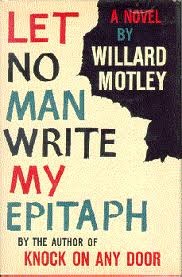

- Let No Man Write My Epitaph, (New York: Random House, 1958).

- Let Noon Be Fair (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1966).

Selected works about Willard Motley:

- “Willard Motley” The Chicago Literary Hall of Fame: 2013 Nominees. Chicago Writers Association. Retrieved 2014-2-20.*

- Fleming, Robert. “Willard Motley” in Bloom, ed., Modern Black Writers. New York: Chelsea House, 1995.