Celebrating the 19th Amendment

The first organized discussion of the right to vote for women was held at the Seneca Falls Convention in July of 1948, where Frederick Douglass, the only black man present, argued for the topic to remain on the list of discussions. Although only a conversation at the convention, the introduction of the topic encouraged suffragists, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, to agree that if women gained the right to vote, they would have more power over the political processes that affected them. By 1851, the topic would become central to initiatives for women and a major topic at future conventions.

At the time, the fight for the right to vote for women was tied to that of black males. Many who were in favor of women gaining voting rights were allies of the movement to abolish slavery. In 1865, people like Wendell Phillips, who was the President of the American Anti-Slavery Society, decided to hone in on black voting rights, excluding women from their reforms initiatives. After the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments passed, granting the right to vote to black men (at least in theory), Stanton, who had been one of the main supporters of the conjoined movement for suffrage, was upset and criticized what had happened saying, “to demand [the black man’s] enfranchisement on the broad principle of natural rights, was hedged about with difficulties, as the logical result of such action must be the enfranchisement of all ostracized classes; not only the white women of the entire country, but the slave women of the South…the only way they could open the constitutional door just wide enough to let the black man pass in, was to introduce the word ‘male’ into the national Constitution.”

The National Women’s Suffrage Association (NWSA), founded in 1869, decided to focus on one goal: getting women the right to vote. Their first approach was to use the constitution as an enabler of their requests. In 1875, the Minor vs. Happersett case was brought to the United States Supreme Court which involved Virginia Minor, who was a leader and advocate for women’s suffrage in Missouri. When Minor went to the ballots to register to vote in 1872, she was turned away because of her gender. Infuriated, Minor took the case to court on the advice of her husband, Francis Minor, and made the argument that as a citizen the 14th Amendment, specifically the clause that guarantees equal privileges and immunities, entailed her the right to vote. The Missouri Supreme Court ruled against her and sided with the registrar, stating that the passing of the right to vote for all citizens was to ensure that freed slaves could register and that it did not implicate any other changes in state laws. Additionally, the Court stated that the penalization of states who did not grant the right to vote to all of its citizens was only granted if the citizen was a man. The Supreme Court upheld the MIssouri Court’s ruling.

Attempts were made by Stanton and Susan B. Anthony to amend the Constitution with the “Petition for Universal Suffrage,” which urged the U.S. to reconsider the restrictions placed on women. The newly founded states of Wyoming (1869), Utah (1870), and Washington (1883), which granted suffrage for women in their constitutions, motivated Stanton and Anthony. In 1873 and 1875, Stanton and Anthony again went to the Supreme Court with the argument that the Constitution did grant women the right to vote, but were shot down both times. Partnered with the NWSA, Stanton and Anthony decided to redirect the movement’s approach and sought to create a new amendment that would achieve their goal.

Throughout the women’s suffrage movement, black women were strategically left out of considerations in the NWSA. They feared that partnering with black women would upset many white women who had become involved from the former Confederate states. The NWSA furthered their segregation of black women by adding regulations that resembled Jim Crow practices and included voter restrictions, such being educated as a prerequisite, in their proposals for a new amendment. The sentiments led to the creation of the Colored Women’s League (CWL), which focused on providing African American women rights that were given to white women and raising the standards of living for blacks at home.

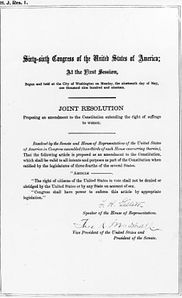

The first draft of the 19th amendment was introduced in January of 1878 by Senator Aaron A. Sargent, who was a lawyer, diplomat, and politician, and had served as a member on the House of Representatives. The words that Sargent drafted were inspired by his wife Ellen Clark Sargent, who was a leading voting rights advocate as well as a close friend to Anthony. Each year after the draft’s creation, the amendment would be voted on and rejected by Congress. The period when it was being rejected is referred to as the “the doldrums” due of the amendment’s state of limbo over those three decades.

Efforts began at the state level, but the intent for federal recognition remained. It was only when Carrie Chapman Catt became president of the NWSA that change began to take place. Catt decided to make the NWSA patriotic and outspokenly favor the U.S.’s role in World War I. She was rewarded for this strategy when President Woodrow Wilson supported suffrage in his 1918 State of the Union address. That year the amendment was voted upon and passed by the House but failed in the Senate by two votes. The following year it was reintroduced and passed by the House of Representatives. A month later the Senate passed it with 56 in favor and 25 against. Northern states immediately ratified the amendment, with Wisconsin, Illinois, and Michigan doing so within six days. The nineteenth amendment was officially passed on August 18, 1920 when Tennessee voted in favor 50-49, becoming the 36th state to ratify the amendment. The morning of August 26, Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby signed the amendment and adopted it into the U.S. Constitution.

It is important to note that after the amendment’s adoption in 1920, women of color continued to face problems at polls in the South. Despite the movement achieving the right to vote for women, many black women continued to be excluded because of Jim Crow laws. These restrictions were not alleviated until the late 1960s, when the Voting Rights Act was passed and criminalized discrimination at the polls.

Despite the setbacks for women of color, the 19th amendment granted women the right to vote for their selected government official and afforded them a say in what was to be done in the country where they had citizenship. Even without complete enfranchisement, it was a cause for celebration.

For more information, visit:

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/19th-amendment-adopted