The Radical and Controversial Orator of Civil Rights: Marcus Garvey

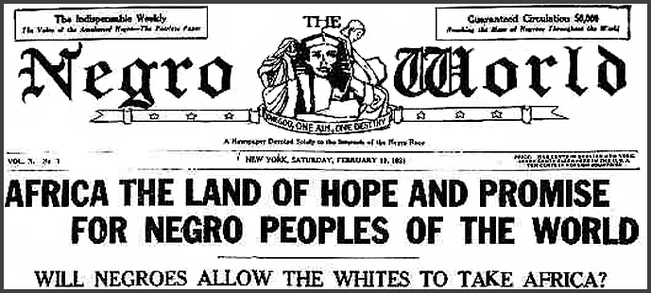

Example of an issue of The Negro World.

Example of an issue of The Negro World.

On August 17, 1887, Marcus Mosiah Garvey, the revolutionary civil rights activist, was born in Saint Ann’s Bay, Jamaica. Garvey is hailed as being an orator for black nationalism and a strong advocate for pan-Africanism, whose ideas helped to create the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the African Communities League in 1914. The organization, combined with Garvey’s powerful charisma, helped to promote the back-to-Africa movement and other movements that encouraged separate nations for black people.

Garvey grew up in Saint Ann’s Bay, Jamaica raised by Sarah Jane Richards, who worked as a domestic worker and farmer, alongside his eleven older siblings. Garvey’s ideals were greatly inspired by his father, Marcus Garvey, Sr., who worked as a stonemason and was rumored to have an enormous library. Garvey recalled that his father was “severe, firm, determined, bold, and strong, refusing to yield even to superior forces if he believed he was right.” These words would come to shape Garvey’s persona later in life. Largely an autodidact, Garvey harvested much of his early education and his passion for literature from his father’s library.

Garvey’s first exposure to politics was when he began working as a printer’s apprentice in Kingston, Jamaica in 1907 and became involved with union activities. After attending a union strike, Garvey developed a passion for political activism, a characteristic that would shape the rest of his life. Sparked by this newfound interest, Garvey decided to take a trip throughout Central America to document the abuses on worker’s rights in 1910. During this period, he lived in both Costa Rica and Panama, writing for newspapers in both countries and documenting worker’s rights. He returned to Jamaica in 1912, where he continued his own education and developed his ideas of pan-Africanism combined with an emphasis on Booker T. Washington’s ideas about economic independence and self-help within the black community.

A few months later, Garvey moved to London, where he attended Birkbeck College from 1912-1914 studying law and philosophy. After attaining his degree, Garvey returned to Jamaica and formed the United Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA), a black nationalist fraternal organization whose mission was to uplift the lives of people of African descent. Garvey’s personal intent for the organization was to “establish one grand racial hierarchy” for blacks, meaning unifying all members of the African diaspora and providing education and economic independence. In 1916, Garvey moved to Harlem in New York City and established a chapter of the UNIA, where the organization gained popularity and invigorated the incipient Harlem Renaissance. By the summer of 1920, the organization claimed four million members and held its first International Convention at Madison Square Garden with an audience of over twenty five thousand members. Alongside UNIA, Garvey started the Liberia project to promote the migration of people of African descent to Liberia, Africa. Liberia was established by the American Colonization Society as a colony for American blacks to “return” to in 1822. Garvey’s project invested in building colleges, industrial plants, and railroads throughout the country to develop it in anticipation of a new influx of black immigrants.

In 1918, four years after UNIA’s founding, Garvey started The Negro World, a weekly newspaper in various languages to broadcast the ideas of the organization globally. Each week the publication focused on an issue that affected people of African descent in a different part of the world and included a specific section for women readers. It was printed until 1933, when publication ended. UNIA also established a company called the Black Star Line in 1919 with Garvey serving as president. It was intended to be a shipping line that would transport goods and people (which was never realized) in the African Global economy. Black Star Line also produced a wine with grapes grown in Ethiopia.

J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI), the precursor to the FBI, wanted to deport Garvey as early as 1919, but could find no cause. The BOI eventually charged him, and three other officers of Black Star Line, with mail fraud in 1922 for having an image of a ship that did not belong to the Black Star Line on a brochure cover and Garvey lost authority of the shipping line. Garvey was arrested in 1925 and chose to represent himself at trial, which did not serve him well. While the other co-defendants were found not guilty, his defense which was aggressive, suggested conspiracies and featured a three-hour long closing argument, led to him being sentenced to five years. He was held at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary for two years until his sentence was commuted and he was deported on the orders of President Calvin Coolidge in 1927.

Back in Jamaica, Garvey continued to fight for equal rights and founded the People’s Political Party (PPP) in 1929, which served as Jamaica’s first modern political party. The PPP administration worked on providing equal rights for workers, students, and providing necessary aid for poor people. Garvey left Jamaica for England in 1935 and stayed there until his death on June 10, 1940. Because of travel restrictions, Garvey’s body was transported back to his homeland twenty years after his death. Today Garvey’s body rests in the National Heroes Park in Kingston, Jamaica.

Despite Garvey’s popularity, many people critiqued him for being extremely radical. One of the most well-known African American leaders and writers of the era, W.E.B. Du Bois, stated that Garvey was “without doubt, the most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America and in the world. He is either a lunatic or a traitor.” Garvey responded by saying Du Bois was prejudiced against him because of his darker skin and accusing his organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, of trying to sabotage Black Star Line. Garvey also tried to engage with the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacists, believing they would support his intent to create a separate nation for black people. Garvey’s remarks were extremely provocative and included thanking white people for Jim Crow Laws, once saying, “I regard the Klan, the Anglo-Saxon clubs and White American societies,

as far as the Negro is concerned, as better friends of the race than all other groups of hypocritical whites put together…every white man is a Klansman as far as the Negro in competition with whites socially, economically and politically is concerned, and there is no use lying.” Because of this, many rejected his ideas and opted for Du Bois’s integrated approach in promoting civil rights.

Although his positions were controversial, Garvey influenced generations to come with his words encouraging black nationalism and pan-Africanism and his emphasis on economic independence. His teaching affected many leaders–even if they did not necessarily agree with all of his positions–such as Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first prime minister who enacted social changes based on his ideas and added a black star to the Ghanaian flag. For years to follow, his teachings and beliefs were labeled under Garveyism, a philosophy that continues to inspire a better future for people of African descent across the globe.