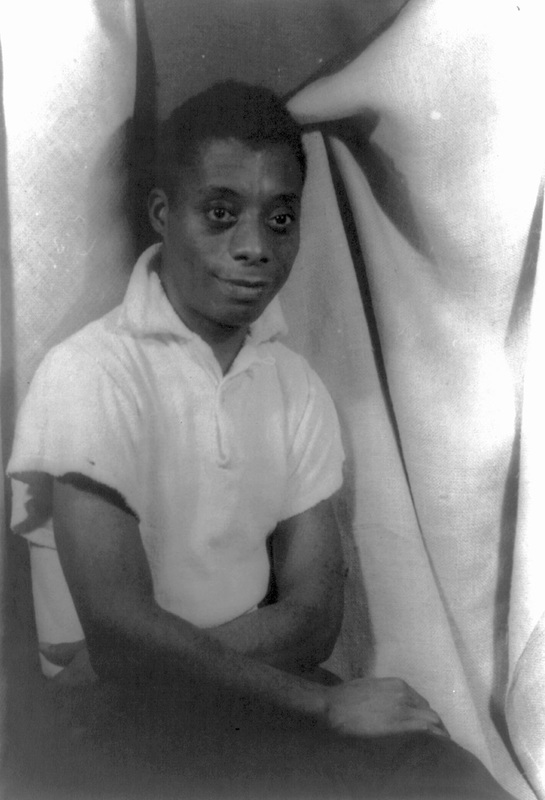

Recognizing James Baldwin’s Legacy

Similarly, Baldwin grew up in a low-income household in Harlem, New York, with parents, Emma Berdis Jones and step-father, David Baldwin. From an early age he was drawn to writing, serving as the literary editor of his high school magazine at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx. In Baldwin’s writings, the relationship he had with his father is an extensive source of hurt. One of Baldwin’s major sources of inspiration and style was his Christian background, which was influenced partially by his father, a former preacher. At the age of fourteen Baldwin began attending meetings at the Pentecostal Church, of which he eventually became a junior minister. By seventeen, Baldwin became disillusioned with Christianity and regarded its teachings as another method for oppressing black people in the United States. Baldwin wrote that “being in the pulpit was like working in the theater; I was behind the scenes and knew how the illusion was worked.”

At the age of eighteen, when Baldwin realized that he no longer believed in the church’s teachings, he was kicked out of his home. From this relationship, Baldwin drew inspiration to write the collection of essays Notes of a Native Son, where he uses his quest to answer and explain his family’s rejection as a leitmotif, also playing off of Richard Wright’s novel, Native Son. Baldwin’s collection of essays depict a protagonist that is well-rounded, in contrast with Wright’s Bigger Thomas, who Baldwin thought was a simplistic incarnation of a black man who perpetuated stereotypes. Much controversy arose between the two writers when Baldwin published the essay, “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” in reference to Wright’s novel, indicating that Native Son lacked credible characters and psychological complexity. After the essay’s publication, the friendship between the two writers ended.

During Baldwin’s teen years, the artist Beauford Delaney served as a mentor, persuading him to believe that blacks could become successful artists. The relationship he fostered with Delaney helped Baldwin realize he was gay. Because of the backlash he knew he would receive as a black, gay man in the United States at that time, he moved Paris, France in 1948 at the age of twenty-four. Although the main reason for Baldwin’s migration was to flee American prejudice, his initial plan was to add a different lens to his writing. Once in Paris, Baldwin became involved with the cultural radicalism of the Left Bank and the French New Wave, a sort of counterculture cultivated in the late 1950s and 1960s. In 1970, Baldwin settled in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the south of France.

Today, many of Baldwin’s works are revered as some of the most remarkable American classics. Among dozens of works, some of his most popular are (in addition to Go Tell It on the Mountain and Notes on a Native Son): Another Country, Giovanni’s Room, No Name in the Street, and Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone. Baldwin is known today for writing whatever he wanted despite the public’s criticism. The plethora of characters throughout his oeuvre consisted of bisexual, white, heterosexual, and gay personas. The novels take on the turbulence of the 1950s and assess the lives of these characters holistically, taking into account the racism and homophobia people experienced at that point in American history. The passion and depth with which Baldwin wrote about the experiences of black and gay people in the United States made him a leading voice for the Civil Rights Movement. Baldwin served as a reporter for the movement after seeing a photo of a young girl standing up to a white mob in attempts to desegregate schools. Although Baldwin did not want to be back in the states, he persevered, writing notable articles such as “The Hard Kind of Courage” and “Nobody Knows My Name” that depicted what was going on in the South for Harper’s Magazine. But although he was avidly involved in the movement, he denounced its name and agreed with Malcolm X’s assertion that if one is a citizen, one should not have to fight for one’s civil rights. The author stated that the Civil Rights Movement should instead be called “the latest slave rebellion.”

The list of American writers Baldwin later influenced is long, including authors such as Maya Angelou, Lorraine Hansberry, Toni Morrison, and Richard Wright, who noted Baldwin as “the greatest black writer in the world.” Morrison, winner of the both the Pulitzer Prize in literature and the American Book Award, remembers Baldwin as her literary inspiration and the person who showed her the potential of writing. Additionally, among critics and scholars Baldwin’s hard-work was rewarded with acclaim even during his lifetime. In 1954 Baldwin won the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship; in 1959 he won the Ford Foundation Fellowship; and in 1963 he won the George Polk Memorial Award, among others.

Since Baldwin’s passing on December 1st, 1987, his writings have been published worldwide and are still known as essential emblems of the American canon.