Massacre Unveiled: Remembering the Negro Fort

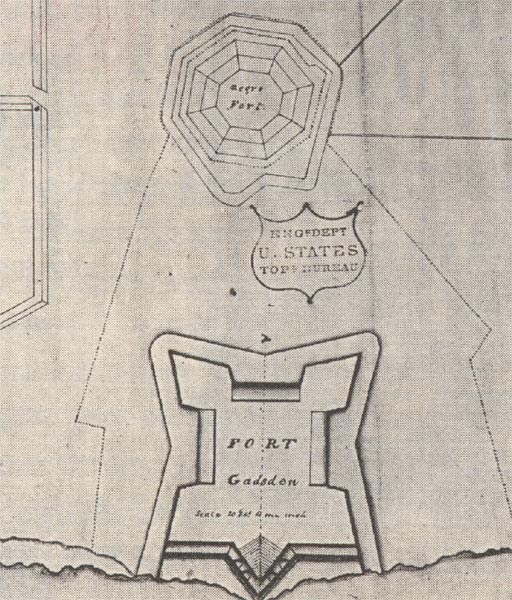

Negro Fort, near the former British Fort Gadsden, was established after the War of 1812, when the British Royal Marines were pushed out of Georgia and settled along the Spanish side of the Apalachicola River. Initially, the fort and the surrounding area was a mix of British, African-Americans, and Native Americans. The African-American population present at Negro Fort was a detached unit of the Corps of Colonial Marines, Marine units composed of former slaves that served in the British Army. After the end of the War of 1812, the British left the area and paid off the Marines, freeing the infantry to reside at the fort. The foundation of the black community with many former slaves so close to America loomed large in the minds of the slave owners across the border. Over the next months, hundreds of freed men and women migrated to the fort and settled there or in the area. Once word began circulating about the autonomous free black community, Georgian plantation owners sent letters to the U.S. government demanding that action be taken against them. Colonel Robert Patterson urged for the fort’s elimination, stating “The service rendered by the destruction of the fort, and the band of negroes who held it is one of great and manifest importance to the United States and particularly those States bordering on the Creek nation, as it had become the rendezvous for runaway slaves.”

In preparation to destroy Negro Fort, Jackson decided to build Fort Scott out of Camp Crawford in June of 1816 at the junction of the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers, where they joined to form the Apalachicola. To receive materials and supplies, boats going to Fort Scott needed to traverse the Apalachicola River–then Spanish territory–passing right next to Negro Fort on the way. During one of the deliveries, two gunboats stopped along the river and were met with an attack by the infantry at the fort. Almost all of the Americans were killed. The event is known as the Watering Party Massacre since they had stopped to refill their canteens. Much controversy exists today surrounding the event, specifically the idea that the event was planned by Jackson to use as justification for destroying Negro Fort. To retaliate, with the permission of the Spanish Governor and under the pretense of “national defense,”Jackson dispatched gunboats to Negro Fort. About 200 black militiamen began preparation for battle. They were accompanied by 30 Seminole warriors under a chief also ready to fight, along with 100 women and children housed in the fort.

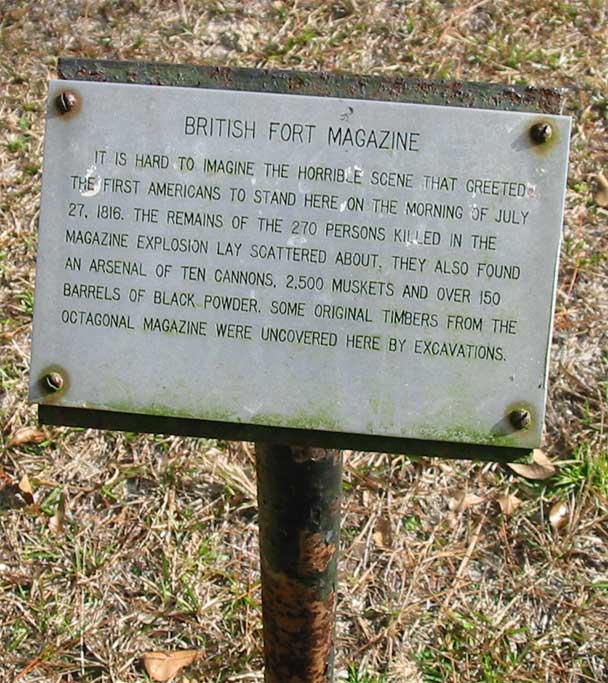

After only a couple minutes of engagement, a cannonball entered the fort’s magazine, where ammunitions were kept, and caused an explosion that destroyed the entire post. The explosion killed 270 men, women, and children. The rest of the population suffered injuries. No casualties for the Americans were noted. General Edmund P. Gaines, who led the American troops, commented that “the explosion was awful and the scene was horrible beyond description.” Many of the survivors at the fort were taken prisoner and placed back into slavery under the claim that the Georgia plantation owners had owned their ancestors.

Both the black commander Garson, a free black man, and the Choctaw chief survived the explosion, but were captured. Garson was killed by an execution squad of the American army, as he was blamed for the Watering Party Massacre, and the Choctaw chief was handed over to the Creeks, who killed and scalped him. The Battle at Negro Fort marks the beginning of the First Seminole War and in no way depicts the end of suffering for the Seminole population in Florida. It also highlights the end of a unique population of people who transcended oppression, forming their community in hopes of freedom and diversity. After mourning the losses at Negro Fort, the Seminole population would mobilize and continue in their pursuit of avenging the forthcoming American expansionism, attesting to their relentless pursuit of freedom and peace.