Setting a Precedent: The African-American 54th Regiment Ships Out

February 16, 1863 recruitment ad from Boston newspaper

February 16, 1863 recruitment ad from Boston newspaper

Today, June 3rd 28 marks the anniversary of when one of the first African-American units in the United States, the 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, arrived in Beaufort, SC, ready for combat during the Civil War in 1863. Following the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation in January, the Governor of Massachusetts John Andrew authorized the formation of a black regiment. Frederick Douglass had been arguing for the enlistment of black soldiers since the outbreak of the war because the government could not deny full citizenship to former slaves who had fought for the country. The Secretary of War had decided that the black units should be led by white officers, however, ten percent of officers in the United States Colored Troops ended up being black.

The 54th was led by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, who came from a prominent abolitionist family and took pains to choose white officers for the regiment who held similar antislavery views. Shaw’s parents and their abolitionist friends worked on recruiting free blacks to serve, many of whom had escaped slavery. Since more volunteers came forward then were necessary, the medical exam they were subjected to was extremely thorough. The regiment ended up including two of Frederick Douglass’s sons and Sojourner Truth’s grandson. They trained at Camp Meigs for two months before departing from Boston on May 28th by steamer. They arrived in Beaufort, SC (which had fallen to the Union Army in late 1861) with much fanfare, however, they were at greater risk than other regiments: Confederate President Jefferson Davis had made a proclamation in late 1862 that any black soldiers or their officers would essentially be subject to capital punishment if captured.

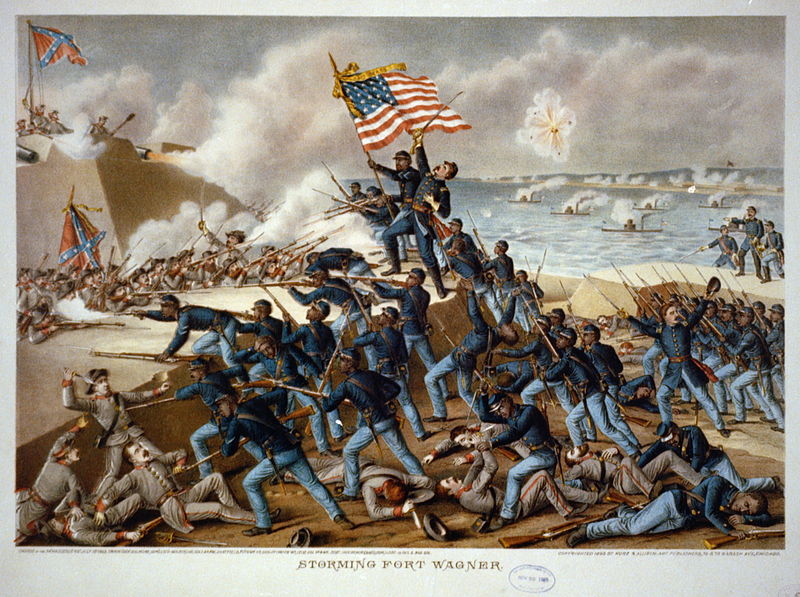

The 54th’s first engagement was a raid into a town in Georgia, followed by a July 16th campaign on James Island, SC where they stopped the Confederates and suffered 42 casualties. Two days later, the regiment had a major battle, attacking Fort Wagner near Charleston. They lost 272 of the 600 men who charged, including Colonel Shaw. The total casualties were the worst that the 54th would suffer during the war. Even though the assault was not successful, word of their bravery spread, driving up African-American enlistment. After Fort Wagner, the unit came under the command of Colonel Edward Hallowell. During the Battle of Olustee while covering a Union retreat, they ended up manually pulling a broken down train car loaded with injured soldiers three miles to Camp Finnegan.

Despite their valor, they were denied proper compensation for their service. At the time of recruitment, they were promised pay equal to that of white soldiers at the rate of $14 a month. Upon arrival in the South, the department said they would only receive $7 per month. Colonel Shaw protested this and after his death, Colonel Hallowell continued the fight. The entire regiment boycotted receiving their pay on principle, even though the state of Massachusetts had offered to pay the difference.

The 54th was led by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, who came from a prominent abolitionist family and took pains to choose white officers for the regiment who held similar antislavery views. Shaw’s parents and their abolitionist friends worked on recruiting free blacks to serve, many of whom had escaped slavery. Since more volunteers came forward then were necessary, the medical exam they were subjected to was extremely thorough. The regiment ended up including two of Frederick Douglass’s sons and Sojourner Truth’s grandson. They trained at Camp Meigs for two months before departing from Boston on May 28th by steamer. They arrived in Beaufort, SC (which had fallen to the Union Army in late 1861) with much fanfare, however, they were at greater risk than other regiments: Confederate President Jefferson Davis had made a proclamation in late 1862 that any black soldiers or their officers would essentially be subject to capital punishment if captured.

The 54th’s first engagement was a raid into a town in Georgia, followed by a July 16th campaign on James Island, SC where they stopped the Confederates and suffered 42 casualties. Two days later, the regiment had a major battle, attacking Fort Wagner near Charleston. They lost 272 of the 600 men who charged, including Colonel Shaw. The total casualties were the worst that the 54th would suffer during the war. Even though the assault was not successful, word of their bravery spread, driving up African-American enlistment. After Fort Wagner, the unit came under the command of Colonel Edward Hallowell. During the Battle of Olustee while covering a Union retreat, they ended up manually pulling a broken down train car loaded with injured soldiers three miles to Camp Finnegan.

Despite their valor, they were denied proper compensation for their service. At the time of recruitment, they were promised pay equal to that of white soldiers at the rate of $14 a month. Upon arrival in the South, the department said they would only receive $7 per month. Colonel Shaw protested this and after his death, Colonel Hallowell continued the fight. The entire regiment boycotted receiving their pay on principle, even though the state of Massachusetts had offered to pay the difference.

On June 18, 1864 Congress authorized equal pay for black soldiers who had been free men as of April 19, 1861. As a Quaker, Colonel Hallowell did not believe in slavery and thus had all of his men swear they free men on April 19, 1861, entitling them to full back pay.

The story of the 54th Regiment was later turned into the 1989 Academy Award-winning film Glory.