More than Just Words: Barbara Jordan’s Strong Politics

Barbara Charline Jordan was born on February 21, 1936 in Houston, Texas to Benjamin M. Jordan, a pastor of the Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church, and Arlyne Patten Jordan, a successful public speaker. She was the youngest of three daughters. She was educated within the Houston public school system, attending Robertson Elementary School and eventually graduating from Phillis Wheatley High School in 1952 with honors.

Inspired to study law after hearing a speech during high school by Edith S. Sampson, the first black U.S. delegate appointed to the United Nations, Jordan attended Texas Southern University and majored in political science and history. She was also a champion debater, often defeating opponents from Ivy League schools such as Yale and Brown. After graduating magna cum laude in 1956, she relocated to Boston where she earned a law degree from Boston University in 1959. Jordan was admitted to both the Massachusetts and Texas bars. After a year teaching at the Tuskegee Institute, the historically black university founded by Booker T. Washington, she decided to return to her hometown of Houston to open her own practice. In order to supplement her income in the early stages, she also worked as an administrative assistant to a local county judge. It was during this time that she met her long-term partner Nancy Earl, an educational psychologist, on a camping trip. Earl would also serve as Jordan’s on-again off-again speechwriter throughout her career.

Jordan’s entrance into the world of politics occurred when she worked for the 1960 presidential campaign of John F. Kennedy. She was instrumental in organizing a get-out-the-vote movement that encouraged citizens within Houston’s 40 predominantly African-American precincts to cast their ballots in local and national elections. In both 1962 and 1964, Jordan campaigned for a seat in the Texas House of Representatives, but was unsuccessful. Two years later, when court-enforced redistricting created a constituency of mainly minority voters, Jordan earned a seat in the Texas Senate. She was initially greeted with hesitation by her fellow senators—who were all white and male—but slowly earned a solid reputation as a powerful legislator vis-à-vis her victories in passing Texas’ first minimum wage law, including anti-discrimination clauses in business contracts, and establishing the Texas Fair Employment Practices Commission. Jordan also became the first black woman in the country to preside over a legislative body when, on March 28, 1972, she was elected president pro tempore of the state senate. One of her responsibilities in this position was also to serve as acting governor when the governor and lieutenant governor were out of the state. She eventually did hold this position for one day on June 10, 1972, making her the first black chief executive in the country.

In 1972, Jordan won election to the U.S. House of Representatives, earning the seat that represented much of downtown Houston, a predominantly African-American and Hispanic-American area. Her opponent in the Democratic primary, Curtis Graves, repeatedly hurled accusations that Jordan too often sided with the white establishment; in defense of her credentials and approach, Jordan responded “I’m not going to Washington and turn things upside down in a day….I’ll only be one of 435. But the 434 will know I am there.” She won both the primary and general elections with over 80% of the vote—a trend that would continue for the next two campaign cycles.

True to her word, Jordan’s presence was immediately noticed in Congress. She was often criticized for her “local” approach to politics, oftentimes overlooking the efforts of civil and women’s rights activists in pursuit of legislation that would directly benefit her constituency. And despite being a member of the Congressional Black Caucus and associated with other House special interest groups, Jordan made sure she was not too closely linked to any of these organizations so that she could continue to pursue her agenda without pushback: “I am neither a black politician nor a woman politician. Just a politician, a professional politician,” she remarked. This practice of congressional influence also translated into her choice of seat within the House Chamber: while many of her fellow CBC members sat to the far left of the room, Jordan sat towards the center in order to be seen and heard, as well as mingle with fellow colleagues. She also made sure to maintain strong ties with members of the Texas delegation, whose influence within the institution could help her push relevant legislation. One of the key bills she got through was the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 which mandated that banks meet the needs all segments of their communities; this meant extending relevant services to poor and minority customers. Additionally, when the Voting Rights Act on 1965 was being reauthorized, she added language to extend the provision to include Latinos, Native Americans, and Asian Americans.

Receiving significant support from fellow Texan and former president Lyndon B. Johnson, Jordan earned a seat on the Judiciary Committee, which she served on throughout her three terms. As a freshman member of the Judiciary Committee, Jordan entered the public eye when the committee held impeachment proceedings against President Richard M. Nixon in relation to the Watergate Scandal. During opening statements for the trial, Jordan eloquently and powerfully remarked, “My faith in the Constitution is whole, it is complete, it is total. I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.” She was perhaps one of the strongest proponents of impeachment, citing reasons for all five articles against President Nixon and stating that, should any one of her fellow members disagree, “then perhaps the eighteenth-century Constitution should be abandoned to a twentieth-century paper shredder.”

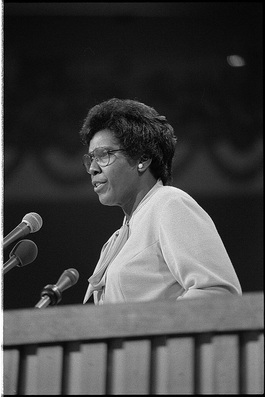

In 1976, Jordan saw her name thrown into a mix that included several other noteworthy politicians as a potential running mate to presidential candidate Jimmy Carter of Georgia. While this did not come to fruition, she did become the first African-American woman keynote speaker at the Democratic National Convention. Jordan famously roused the crowd during her speech, stating that “we cannot improve on the system of government handed down to us by the founders of the Republic, but we can find new ways to implement the system and to realize our destiny.”

Jordan completed her final term in Congress in 1979, making the difficult decision to ret

ire following a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. She then turned her focus towards the education of aspiring policy makers and politicians, teaching for a period of time at the University of Texas at Austin and becoming the Lyndon B. Johnson Centennial Chair of Public Policy in 1982. In 1994, Jordan was appointed by President Bill Clinton as head of the Commission on Immigration Reform, as well as awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Jordan passed away in her home state of Texas on January 17, 1996 from pneumonia, resulting from complications with her battle against leukemia.

Barbara Jordan will forever be remembered as the epitome of the American politician. Dedicated to the Constitution and gifted with supreme powers of oration as well as a precise internal political compass, Jordan and her legacy serve as a lesson for young aspiring politicians everywhere that the promise of a politician to his or her constituency is not to push a personal agenda, but to push the agenda of the common people and uphold the law of the land above all else. In this regard, Jordan remains unique.