Behind the Scenes: The Work of Augustus Hawkins

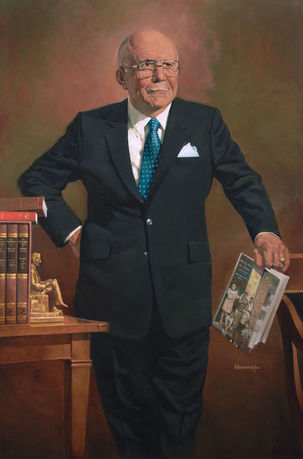

Today for Black History Month, we honor Augustus F. Hawkins, a well-known Democrat politician and the first African-American from California to serve in the United States Congress. Throughout his long career, he became known as the “Silent Warrior” for his behind the scenes commitment to the issues of education and unemployment and had a hand in the authorship of over 300 pieces of innovative and groundbreaking legislation.

Augustus (Gus) Freeman Hawkins was born on August 31, 1907 in Shreveport, Louisiana as the youngest of five children to Nyanza Hawkins and Hattie Freeman. The family relocated to Los Angeles, California in 1918, and Hawkins graduated from Jefferson High School in 1926. He went on to attend the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in economics in 1931. He had intended to pursue graduate education in civil engineering, but his own lack of funding coupled with the Great Depression of the 1930s made this dream impossible. Instead, he partnered with his brother, Edward, to open a real estate company and began taking courses at the University of California’s Institute of Government—a move that sparked his interest in politics. Hawkins supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1932 presidential bid, as well as the 1934 gubernatorial campaign of Upton Sinclair, the famous journalist (later a Pulitzer Prize winner) and socialist. He entered the world of politics himself that same year after winning a seat in the California State Assembly, defeating Frederick Roberts, a 16-year veteran Republican and the great-grandson of Sally Hemings and President Thomas Jefferson, who he criticized for the length of his stay in office. Interestingly enough, Hawkins would also be come to know for the longevity of his service in the state assembly. He married his first wife, Pegga Adeline Smith on August 28, 1945; he would later remarry Elise Taylor in 1977 after Pegga’s death.

During his time in the California State Assembly from 1935 to 1965, Hawkins focused his legislative record on catering to the interests of his constituents, who were predominantly African-American and Latino. He chaired the joint legislative organization committees and introduced a fair housing act, a fair employment practices act, provisions for workmen’s compensation for domestics, and additional legislation for disability insurance and low-cost housing—all measures that he would continue to champion in the U.S. Congress. Although his measures did not enjoy much support within the Democratic Party, Hawkins was nonetheless able to pass a lot of his proposed legislation. In 1958, Hawkins campaigned to become Speaker of the California State Assembly, but lost to Ralph M. Brown of Modesto, California. Despite his loss, he was appointed chairman of the powerful rules committee—a position he held for two years.

Hawkins made the decision in 1962 to run for a seat in the U.S. Congress, feeling that his position as a Congressman would allow him to have greater impact within the state Assembly. He competed in the Democratic primary to represent a new majority-black congressional district including central Los Angeles, handily defeating his three opponents after an endorsement from President John F. Kennedy. He went on to claim victory in the general election beating Republican attorney Herman Smith with 85% of the vote to win a Congressional seat in the 88th Congress, becoming the first black representative from California. He commented of his shift to the House of Representatives that, “It’s like shifting gears—from the oldest man in the Assembly in years of service to a freshman in Congress.” Between 1963 and 1991, Hawkins would serve the 21st District of California (1963-75) and eventually the 29th District (1975-1991). He was consistently re-elected with a strong majority, capturing over 80% of the vote every time. His initial victory also made him the first black elected representative west of the Mississippi River.

As soon as he began his term in Congress, Hawkins immediately began work on influential legislation. He sat on the Education and Labor Committee, which was chaired by Adam Clayton Powell at the time, eventually rising to chairman and was a strong proponent of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society initiative. He authored legislation such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination by an employer on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin and established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a federal agency to administer and enforce those provisions. When it passed, he noted that, “It is incomplete and inadequate; but it represents a step forward.” In 1964, he embarked on a tour of the South with three other Representatives in order to advocate for African-American voter registration and witness discrimination.

The following year the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, prohibiting discrimination in voting, outlawing literacy tests and similar devices and requiring certain jurisdictions to receive prior approval from the Justice Department before enacting any provisions that would affect voting. Five days after this landmark legislation became law, Hawkins faced an issue of a very different nature when the Watts Riots erupted in his own district. The first of many race riots that occurred in the 1960s, the Watts Riots arose from the drunk driving arrest of a black motorist, which escalated into an argument and then a fight, giving rise to community mobs that resulted in six days of looting and arson. 4,000 members of the California National Guard were needed to help suppress the rioting, which ultimately led to 34 deaths and over $40 million in damage.

The riots revealed issues surrounding increased poverty—an issue that Hawkins pleaded Congress to address immediately, saying, “The trouble is that nothing has ever been done to solve the long–range underlying problems.” One of those underlying problems was fair housing: L.A. did not have the official segregation of the South, but like many cities across the country it had restrictive covenants based on race that prevented minorities from renting and buying in many areas and had been legally enforced in the past. Although the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled these unconstitutional in Shelley vs. Kraemer in 1948, many areas of Los Angeles still had informal restrictions in place. However, fair housing was a controversial issue in America, as many white individuals did not want to live next to blacks, Asians or Latinos. The riots did not help the case for fair housing as the black individuals who had experienced benefits from the Great Society legislation were blamed as having disrupted the “law and order” of America, making them much less desirable as possible neighbors. Further housing reform was on the a

genda following the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but the Watts Riots stalled its progress. It was not passed until the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, which also resulted in rioting across the nation.

Hawkins was also an outspoken opponent of the Vietnam War and America’s overall foreign policy programs, remarking that the United States made a mistake in “believing we can impose our way of life on other people.” Whilst serving on a select committee assigned to provide the House with specialized information about the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, Hawkins and Democrat William Anderson of Tennessee, visited the country in 1970, seeing a civilian prison on Con Son Island and witnessed all prisoners, including women and children, locked in “tiger cages” and suffering from extreme forms of malnutrition. Returning to the United Sates, Hawkins pushed for Congress to condemn the inhumane treatment of these prisoners. The visit also further convinced him that American troops should be removed from Vietnam.

As a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus, Hawkins held the position of vice chairman from 1971 to 1973. However, he did not play a significant role in the organization, criticizing the CBC as being, “85 percent social and 15 percent business.” Instead he focused on passing actual legislation: Hawkins was instrumental in passing the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974, which provides specific protections to youth who commit criminal offences; the 1978 Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, which offered training and jobs in the public service to those with low incomes and long-term unemployment, creating 660,000 new jobs; and the 1978 Pregnancy Disability Act, which outlawed discrimination against women on the basis of pregnancy. However, he is best known for the 1978 Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment act, introduced alongside Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota. Stemming from the economic downturn of 1975 which caused the unemployment rate to increase to 8.5%, and almost 14% among non-whites, the bill required Congress to set a goal of 4% unemployment by 1983 and that Congress be provided with a complete testimony about the present economic state, although it did not include substantive provision about how to achieve these measures. However, by the time President Jimmy Carter signed it into law, it was regarded mostly as a “symbolic” step.

Towards the end of his career, Hawkins began to experience greater pushback on legislation from conservative presidents such as Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, who viewed his positions and approaches as outdated. His greatest blow came from President George H. W. Bush, who vetoed his Civil Rights Act of 1990, which would have increased job protection for minorities and women by placing the burden of proof regarding discriminating hiring practices on the employer rather than the employee. Following this defeat, at the end of the 101st Congress in 1991, Hawkins made the monumental decision to retire. Bush signed an amended, weakened version titled the Civil Rights Act of 1991 following Hawkins’ retirement. He remained living on Capitol Hill for the remainder of his life and was the oldest living person to have served in Congress until his death at the age of 100 on November 10, 2007 in Bethesda, Maryland.

Throughout his career, Augustus Hawkins repeated that “the leadership belongs not to the loudest, not to those who beat the drums or blow the trumpets, but to those who day in and day out, in all seasons, work for the practical realization of a better world—those who have the stamina to persist and remain dedicated.” By living according to those words—building coalitions and consensus with out losing sight of the overarching goal, he truly became the “silent warrior.” He has left a tremendous legacy spanning fair housing, civil rights, unemployment benefits, and work place discrimination that affects all of us today and has demonstrably bettered this country.

Augustus (Gus) Freeman Hawkins was born on August 31, 1907 in Shreveport, Louisiana as the youngest of five children to Nyanza Hawkins and Hattie Freeman. The family relocated to Los Angeles, California in 1918, and Hawkins graduated from Jefferson High School in 1926. He went on to attend the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in economics in 1931. He had intended to pursue graduate education in civil engineering, but his own lack of funding coupled with the Great Depression of the 1930s made this dream impossible. Instead, he partnered with his brother, Edward, to open a real estate company and began taking courses at the University of California’s Institute of Government—a move that sparked his interest in politics. Hawkins supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1932 presidential bid, as well as the 1934 gubernatorial campaign of Upton Sinclair, the famous journalist (later a Pulitzer Prize winner) and socialist. He entered the world of politics himself that same year after winning a seat in the California State Assembly, defeating Frederick Roberts, a 16-year veteran Republican and the great-grandson of Sally Hemings and President Thomas Jefferson, who he criticized for the length of his stay in office. Interestingly enough, Hawkins would also be come to know for the longevity of his service in the state assembly. He married his first wife, Pegga Adeline Smith on August 28, 1945; he would later remarry Elise Taylor in 1977 after Pegga’s death.

During his time in the California State Assembly from 1935 to 1965, Hawkins focused his legislative record on catering to the interests of his constituents, who were predominantly African-American and Latino. He chaired the joint legislative organization committees and introduced a fair housing act, a fair employment practices act, provisions for workmen’s compensation for domestics, and additional legislation for disability insurance and low-cost housing—all measures that he would continue to champion in the U.S. Congress. Although his measures did not enjoy much support within the Democratic Party, Hawkins was nonetheless able to pass a lot of his proposed legislation. In 1958, Hawkins campaigned to become Speaker of the California State Assembly, but lost to Ralph M. Brown of Modesto, California. Despite his loss, he was appointed chairman of the powerful rules committee—a position he held for two years.

Hawkins made the decision in 1962 to run for a seat in the U.S. Congress, feeling that his position as a Congressman would allow him to have greater impact within the state Assembly. He competed in the Democratic primary to represent a new majority-black congressional district including central Los Angeles, handily defeating his three opponents after an endorsement from President John F. Kennedy. He went on to claim victory in the general election beating Republican attorney Herman Smith with 85% of the vote to win a Congressional seat in the 88th Congress, becoming the first black representative from California. He commented of his shift to the House of Representatives that, “It’s like shifting gears—from the oldest man in the Assembly in years of service to a freshman in Congress.” Between 1963 and 1991, Hawkins would serve the 21st District of California (1963-75) and eventually the 29th District (1975-1991). He was consistently re-elected with a strong majority, capturing over 80% of the vote every time. His initial victory also made him the first black elected representative west of the Mississippi River.

As soon as he began his term in Congress, Hawkins immediately began work on influential legislation. He sat on the Education and Labor Committee, which was chaired by Adam Clayton Powell at the time, eventually rising to chairman and was a strong proponent of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society initiative. He authored legislation such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination by an employer on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin and established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a federal agency to administer and enforce those provisions. When it passed, he noted that, “It is incomplete and inadequate; but it represents a step forward.” In 1964, he embarked on a tour of the South with three other Representatives in order to advocate for African-American voter registration and witness discrimination.

The following year the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, prohibiting discrimination in voting, outlawing literacy tests and similar devices and requiring certain jurisdictions to receive prior approval from the Justice Department before enacting any provisions that would affect voting. Five days after this landmark legislation became law, Hawkins faced an issue of a very different nature when the Watts Riots erupted in his own district. The first of many race riots that occurred in the 1960s, the Watts Riots arose from the drunk driving arrest of a black motorist, which escalated into an argument and then a fight, giving rise to community mobs that resulted in six days of looting and arson. 4,000 members of the California National Guard were needed to help suppress the rioting, which ultimately led to 34 deaths and over $40 million in damage.

The riots revealed issues surrounding increased poverty—an issue that Hawkins pleaded Congress to address immediately, saying, “The trouble is that nothing has ever been done to solve the long–range underlying problems.” One of those underlying problems was fair housing: L.A. did not have the official segregation of the South, but like many cities across the country it had restrictive covenants based on race that prevented minorities from renting and buying in many areas and had been legally enforced in the past. Although the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled these unconstitutional in Shelley vs. Kraemer in 1948, many areas of Los Angeles still had informal restrictions in place. However, fair housing was a controversial issue in America, as many white individuals did not want to live next to blacks, Asians or Latinos. The riots did not help the case for fair housing as the black individuals who had experienced benefits from the Great Society legislation were blamed as having disrupted the “law and order” of America, making them much less desirable as possible neighbors. Further housing reform was on the a

genda following the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but the Watts Riots stalled its progress. It was not passed until the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, which also resulted in rioting across the nation.

Hawkins was also an outspoken opponent of the Vietnam War and America’s overall foreign policy programs, remarking that the United States made a mistake in “believing we can impose our way of life on other people.” Whilst serving on a select committee assigned to provide the House with specialized information about the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, Hawkins and Democrat William Anderson of Tennessee, visited the country in 1970, seeing a civilian prison on Con Son Island and witnessed all prisoners, including women and children, locked in “tiger cages” and suffering from extreme forms of malnutrition. Returning to the United Sates, Hawkins pushed for Congress to condemn the inhumane treatment of these prisoners. The visit also further convinced him that American troops should be removed from Vietnam.

As a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus, Hawkins held the position of vice chairman from 1971 to 1973. However, he did not play a significant role in the organization, criticizing the CBC as being, “85 percent social and 15 percent business.” Instead he focused on passing actual legislation: Hawkins was instrumental in passing the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act of 1974, which provides specific protections to youth who commit criminal offences; the 1978 Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, which offered training and jobs in the public service to those with low incomes and long-term unemployment, creating 660,000 new jobs; and the 1978 Pregnancy Disability Act, which outlawed discrimination against women on the basis of pregnancy. However, he is best known for the 1978 Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment act, introduced alongside Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota. Stemming from the economic downturn of 1975 which caused the unemployment rate to increase to 8.5%, and almost 14% among non-whites, the bill required Congress to set a goal of 4% unemployment by 1983 and that Congress be provided with a complete testimony about the present economic state, although it did not include substantive provision about how to achieve these measures. However, by the time President Jimmy Carter signed it into law, it was regarded mostly as a “symbolic” step.

Towards the end of his career, Hawkins began to experience greater pushback on legislation from conservative presidents such as Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, who viewed his positions and approaches as outdated. His greatest blow came from President George H. W. Bush, who vetoed his Civil Rights Act of 1990, which would have increased job protection for minorities and women by placing the burden of proof regarding discriminating hiring practices on the employer rather than the employee. Following this defeat, at the end of the 101st Congress in 1991, Hawkins made the monumental decision to retire. Bush signed an amended, weakened version titled the Civil Rights Act of 1991 following Hawkins’ retirement. He remained living on Capitol Hill for the remainder of his life and was the oldest living person to have served in Congress until his death at the age of 100 on November 10, 2007 in Bethesda, Maryland.

Throughout his career, Augustus Hawkins repeated that “the leadership belongs not to the loudest, not to those who beat the drums or blow the trumpets, but to those who day in and day out, in all seasons, work for the practical realization of a better world—those who have the stamina to persist and remain dedicated.” By living according to those words—building coalitions and consensus with out losing sight of the overarching goal, he truly became the “silent warrior.” He has left a tremendous legacy spanning fair housing, civil rights, unemployment benefits, and work place discrimination that affects all of us today and has demonstrably bettered this country.