Public Defender: Shirley Chisholm’s Lonely Battle

Shirley Anita St. Hill was born on November 24, 1924 in Brooklyn, New York. She was the oldest of four daughters born to Charles St. Hill, a factory laborer from Guyana, and Ruby Seale St. Hill, a seamstress from Barbados. She spent a portion of her childhood living on her grandparents’ farm in Barbados, while her parents remained in the United States to work through the Great Depression; this is where she acquired the slight British accent that she would carry throughout her life. Of this time, Chisholm recalls the influence of her grandmother: “Granny gave me strength, dignity, and love. I learned from an early age I was somebody.”

Upon returning to the United States, Chisholm entered the public school system, where she excelled with high grades. She attended Brooklyn College on a scholarship and was a member of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority. Chisholm graduated cum laude in 1946 with a B.A. in sociology, and began working as a teacher at a nursery school, eventually becoming its director. She met her husband, Conrad O. Chisholm, in the late 1940s, and the two wed in 1949 in a West Indian style wedding. Shirley returned to education three years later—this time, her own—receiving a master’s degree in early childhood education from Columbia University. She went on to serve as an educational consultant for New York City’s Division of Day Care for five years, becoming interested in politics and working with political groups such as the Bedford-Stuyvesant Political League and the League of Women Voters. During this time, she became a well-known figure on early education and child welfare.

In 1964, Chisholm was elected as a Democratic member to the New York State Assembly, serving from 1965 to 1968. During her tenure, she succeeded in extending unemployment benefits to domestic workers as well as sponsoring the introduction of a SEEK (Search for Education, Elevation, and Knowledge) program, which allowed disadvantaged students to attend college with the aid of intensive remedial education.

In 1968, a court-ordered reapportionment plan created a new Congressional district in her Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. Having grown up there and having strong ties the community, Chisholm was convinced to run for Congress. She faced tough competition from a pool of three other African-American candidates, which included a civil court judge and former district leaders. However, she campaigned with her own personal style: roaming the district in a small sound truck proclaiming, “Ladies and Gentlemen … this is fighting Shirley Chisholm coming through,” then parking outside of housing projects to have direct interactions with people. She eventually won the primary, beating her closest competitor by 800 votes.

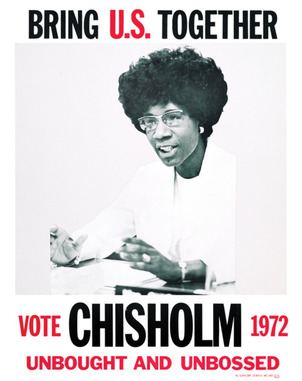

In the general election, Chisholm faced the Republican-Liberal candidate James Farmer. The two were aligned on several important issues, such as housing, employment, education, and opposition to the Vietnam War; furthermore, Farmer had been an important Civil Rights figure, organizing Freedom Riders in the early ‘60s and cofounding the Congress for Racial Equality. But they differed on the issue of gender: he asserted that, “women have been in the driver’s seat” in the community for too long, and that it would be of more benefit to have a “man’s voice” representing them. Chisholm, whose motto was “unbought and unbossed,” emphasized that men had failed in their representation of the district before and that the people of Bed-Stuy had called upon her to finally bring about change. Given the district’s overwhelming liberal majority, as well as Chisholm’s effective campaigning, Chisholm was victorious in the general election, earning 67% of the vote.

Chisholm did not have the easiest transition into the House. Outspoken and determined, Chisholm immediately began working towards solutions for issues she was passionate about. She lashed out against the war in Vietnam and spoke out when she was first assigned to the Committee on Agriculture, where she felt she was not directly related to her constituents. However, she made the most of this position, expanding food stamps and creating the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which enabled low-income women, infants, and children to have access to nutritious foods. Chisholm also pushed for the same issues that had interested her when she was a community activist, sponsoring increases in federal funding to extend daycare-operating hours, and guaranteeing a minimum annual income for families.

Chisholm was also a supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), a proposed constitutional amendment that would have guaranteed equal rights for women. First introduced in 1923 soon after women gained the right to vote with the 19th Amendment, came to prominence again in the 1970s with the rise of Second-wave feminism. Chisholm defended it on the House floor, saying “Discrimination against women, solely on the basis of their sex, is so widespread that is seems to many persons normal, natural and right.” After, it passed both the House and the Senate and was sent to state legislatures for approval. However, after being ratified in 30 states, conservative forces organized against the ERA, espousing the virtues of women’s traditional roles as wives and mothers and threatening female military conscription, eventually defeating its passage.

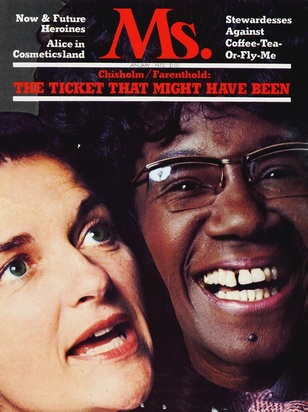

The January, 1973 Ms. Magazine cover.

The January, 1973 Ms. Magazine cover.

From 1971 to 1977, she served on the Committee on Education, and later on the Committee on Organization Study and Review. During this time, she sponsored a national student lunch bill and organized her colleagues in order to override President Gerald Ford’s veto for its passage. Between 1977 and 1981, Chisholm served as Secretary of the Democratic Caucus. She also became the first black woman and second woman overall to serve on the Rules Committee in 1977. Chisholm was also a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) and Congresswomen’s Caucus. She became known as a sort of trailblazer in the house, often butting heads with the establishment to complete her agenda.

Still eager to enact change at the national level, Chisholm announced her intention to run for the 1971 Democratic nomination for President and, in doing so, became the first black politician from a major party to run for president and the first female Democrat. Given her time in the House and her background, Chisholm asserted that she could represent the interests of blacks and the inner-city poor. While campaigning, she described her run thusly, “I am a candidate for the Presidency of the United States. I make that statement proudly, in the full knowledge that, as a black person and as a female person, I do not have a chance of actually gaining that office in this election year. I make that statement seriously, knowing that my candidacy itself can change the face and future of American politics — that it will be important to the needs and hopes of every one of you — even though, in the conventional sense, I will not win.” She politicked across the country, gaining increased visibility, and eventually earned 152 delegate votes, or 10 percent of the total vote, at the Democratic National Convention.

Although she became quite a well-recognized national figure as a result of her run, her bid for President caused a strain within the House and the CBC. Black male politicians criticized her for betraying the interests of the CBC by developing a wider coalition, including women, welfare recipients, white liberals, and Hispanics. She also was met with resistance from other female members of the House, a few of whom endorsed her opponent. She said of the experience, “When I ran for the Congress, when I ran for president, I met more discrimination as a woman than for being black. Men are men.” In Chisholm’s office, all of her staffers were women; half of them African-American.

In 1976, she faced competition in her party primary from New York City Councilman Samuel D. Wright, who argued that her absenteeism from the House of Representatives (partially due to her Presidential bid) made her a bad choice for re-election. However, she restated her position as a legislative trailblazer, and eventually won the general election, garnering 83% of the vote. From 1977-81 she was selected for party leadership, becoming the Secretary of the House Democratic Caucus.

Towards the end of 1970s, many Democrats and other representatives speculated that Chisholm would not seek re-election. In 1982, she herself confirmed this theory, citing personal reasons for her decision to leave, one of which was spending time with her second husband, Arthur Hardwick, Jr. A second reason was the increased tide of conservatism sweeping over the country following the election of President Ronald Reagan. She also felt that her actions within the House were often misunderstood. Especially among the CBC, she felt that her colleagues denigrated her attempts to build larger coalitions, remarking, “We still have to engage in compromise, the highest of all arts. Blacks can’t do things on their own, nor can whites. When you have black racists and white racists it is very difficult to build bridges between communities.”

Following her exit from Congress, Chisholm took up residence in Williamsville, New York. She became the Purington Chair at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, teaching classes in a variety of subjects. She also toured the country giving speeches and encouraging local organizing efforts. Chisholm also helped to cofound the National Political Congress of Black Women and assisted Jesse Jackson in his presidential bids in 1984 and 1988. She was nominated as the United States Ambassador to Jamaica by President Clinton, but refused due to her health. On January 1st, 2005, Chisholm passed away in Ormond Beach, Florida at the age of 80.

Shirley Chisholm was an exemplary woman who defied the norms of the political process in order to enact real and meaningful change. Her background as a self-proclaimed Barbadian American and community activist allowed her to understand the issues facing her community of Bedford-Stuyvesant and successfully represent the district on the national stage, fighting for the rights of women, children and the poor. Furthermore, her ability to negotiate and seek unconventional solutions to problems facing many Americans earned her many more victories than failures. Last but not least, we cannot forget the precedent that she set in her bids for the Democratic presidential nomination—one that is particularly relevant in the present day. Although self-described as “a pragmatic politician,” Chisholm will forever be remembered as the outside-the-box trailblazer who left a lasting mark on the world of politics in the United States.