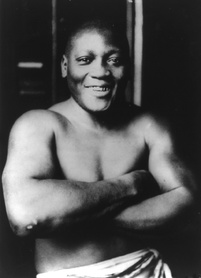

Hard Road to Glory Moments: Remembering Jack Johnson

Before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball, another Jack broke the color barrier in boxing. Jack Johnson, cited by Arthur Ashe as one of “the most famous people on this earth in his time, and surely in all of the African diaspora” was the first black heavy weight champion.

At the turn of the century, boxing was a very popular sport and also mostly segregated. Johnson was crowned the best black boxer alive in 1903, but it took years to get a chance at the world heavyweight belt, held by white boxer Jim Jeffries who refused to fight a black man. He finally retired in 1905 at which point the belt passed to Marvin Hart, followed by Tommy Burns. Johnson provoked Burns to fight him in Australia in 1908 after following him from country to country around the world. He handily won the match infuriating many commentators, spectators and fans.

It was against this backdrop that Jim Jeffries came out of retirement to prove the supremacy of white boxers in a match against Johnson. It was also the richest proposition in sports history. When Jeffries, billed as the “Great White Hope,” Johnson and the promoters signed the terms for the fight, it was the largest legitimate business deal consummated by an African-American to date.

The fight was held in San Francisco on July 4, 1910. Ending in the fifteenth round, Jeffries went down and Johnson became the undisputed world heavyweight champion. In response, there were race riots across the country: 13 black Americans were murdered and countless more injured due to the emotional significance—humiliation—of the “Great White Hope” losing to a black man.

On top of Johnson’s athletic prowess, he was also a pompous and larger-than-life figure, which helped propel him to become one of the first black iconic celebrities in America. He would frequently taunt other men, not just opponents. In an era where blacks were depicted in the media as imbeciles, criminals or victims of a lynch mob, it was novel to have a black man in the mainstream headlines for his achievements.

However, Johnson led a tumultuous life. He dated and married white women, which was very controversial at the time. One of his wives killed herself in 1912 and a month later he was shot in the foot during a dispute. In 1912 he was charged with violating the Mann Act, which prohibited transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes. Eventually, he was convicted and sentenced to prison, although many believe his trial was trumped up as a rebuke to his notorious public persona and disregard for social conventions. He skipped bail and lived abroad for seven years, before turning himself in at the Mexican border in 1920.

At the turn of the century, boxing was a very popular sport and also mostly segregated. Johnson was crowned the best black boxer alive in 1903, but it took years to get a chance at the world heavyweight belt, held by white boxer Jim Jeffries who refused to fight a black man. He finally retired in 1905 at which point the belt passed to Marvin Hart, followed by Tommy Burns. Johnson provoked Burns to fight him in Australia in 1908 after following him from country to country around the world. He handily won the match infuriating many commentators, spectators and fans.

It was against this backdrop that Jim Jeffries came out of retirement to prove the supremacy of white boxers in a match against Johnson. It was also the richest proposition in sports history. When Jeffries, billed as the “Great White Hope,” Johnson and the promoters signed the terms for the fight, it was the largest legitimate business deal consummated by an African-American to date.

The fight was held in San Francisco on July 4, 1910. Ending in the fifteenth round, Jeffries went down and Johnson became the undisputed world heavyweight champion. In response, there were race riots across the country: 13 black Americans were murdered and countless more injured due to the emotional significance—humiliation—of the “Great White Hope” losing to a black man.

On top of Johnson’s athletic prowess, he was also a pompous and larger-than-life figure, which helped propel him to become one of the first black iconic celebrities in America. He would frequently taunt other men, not just opponents. In an era where blacks were depicted in the media as imbeciles, criminals or victims of a lynch mob, it was novel to have a black man in the mainstream headlines for his achievements.

However, Johnson led a tumultuous life. He dated and married white women, which was very controversial at the time. One of his wives killed herself in 1912 and a month later he was shot in the foot during a dispute. In 1912 he was charged with violating the Mann Act, which prohibited transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes. Eventually, he was convicted and sentenced to prison, although many believe his trial was trumped up as a rebuke to his notorious public persona and disregard for social conventions. He skipped bail and lived abroad for seven years, before turning himself in at the Mexican border in 1920.

Johnson continued to fight professionally until he was 60, fighting 114 fights with 80 wins. Today, June 10th, marks the anniversary of his passing due to a fatal car crash in North Carolina, 1946. Still known as one of the greatest boxers to step into the ring, we remember Jack Johnson for his boldness and unapologetic approach to life and the limelight.

Watch a snippet of the match between Johnson and Jeffries

Visit PBS for more information on Jack Johnson