William Attaway: Blood on the Forge and the Great Migration

William Attaway was most well-known for the novel, Blood on the Forge, a story of three brothers who escape sharecropping life in the south to migrate north and find a new life of freedom in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Exemplifying a common pattern of movement by many black Americans in the 1920s and 1930sknown as the ‘Great Migration,’ the Moss brothers arrive to work in the steel mills in the north, only to discover inequality in a different context in their new life.

The trajectory of the novel mirrors Attaway’s own life and migration. He was born in Mississippi in 1911 to William S. Attaway, a physician, and Florence Parry Attaway, a teacher. As part of the northward flow during the great migration, his family moved from Mississippi to Chicago when he was six years old to find opportunities in the city and escape the segregated South.

Attaway had little interest in academics as a child. He attended a vocational high school and was set on becoming an auto mechanic. According to various sources, his life changed when he read a poem by Langston Hughes in English class. Not only was he moved, but upon discovering that Langston Hughes was a black poet, he was inspired to apply himself academically and excel throughout the rest of his high school career.

Attaway attended college briefly but was forced to withdraw due to his father’s death. He spent several years traveling and working odd jobs. In 1935 he returned to Chicago and co-authored the Federal Writers’ Project Guide for Illinois. During this time he befriended fellow author and contemporary, Richard Wright. In 1935 Attaway returned to college, completed his degree, and moved to New York.

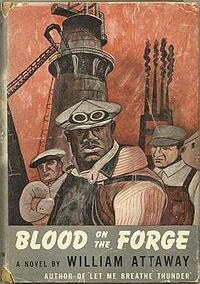

For a brief time, he continued with several odd jobs including acting, and toured with his sister’s acting troupe for a brief time. He continued to write dramas and novels and send them to publishing houses to elicit interest in his work. His first novel, Let Me Breathe Thunder, was published in 1939. Shortly thereafter he obtained a grant from the Julius Rosenwald Fund to produce his most famous work: Blood on the Forge.

Blood on the Forge, like many novels about the Great Migration, was centered on themes of class struggles and the hardships black American workers faced during the period of the Great Depression. The characters of the three Moss brothers, Big Matt, Chinatown, and Melody, personify the issues of class and race-driven economic disparities of the Depression era. The brothers escape a miserable life as sharecroppers in Kentucky to work in a steel mill in Pittsburgh in anticipation of better wages and working conditions. Instead, they arrive at the mill to find a different set of treacherous conditions that challenge their physical endurance, their dignity, and their spirit. In addition, in the steel mill the men encounter overt hostility from other workers. It turns out that the mill solicited large numbers of black men to come north with the promise of more freedom, improved wages and conditions, but in reality, used them as pawns in an attempt to break a strike organized by current workers, and did not deliver on any of the aforementioned promises. Instead, the brothers faced a hostile work environment with many of the immigrant and white workers who were fearful that this new influx of workers from the South would usurp their jobs.

In a climactic scene there is a race riot at the mill where Big Mat dies and the other two brothers are severely injured. According to Carl Milton Hughes, “Modern tragedy takes into account the failures and frustrations of the life of the ordinary man in highly industrialized civilization. The machine robs man of that sense of immanence that he had in less highly developed epochs” (The Negro Novelist, p. 83). In addition to the rise and fall of man in industrialized society, Attaway utilizes unique character traits in each of the brothers to highlight the decreasing connection between their life and culture as black Americans in Kentucky and their adaptation to life in the North. Big Mat’s brute strength and religious piety no longer suffice as a consolation or raise his spirit in difficult times. Similarly, Melody does not strum his guitar as he used to, and Chinatown’s stories, representative of the oral tradition prominent in Southern black culture, cease to exist as they did when he is blinded in the explosion and can no longer use visual cues to assess his environment.

Blood on the Forge was the last of Attaway’s novels. He later turned to writing for more commercial purposes in radio, films and television. He wrote a number of songs, including the famous “Day-O (Banana Boat Song)” for Harry Belafonte, in whose home he was married in 1962. He married Frances Settele, a white woman, during a very racially charged period in the United States. Several years later, they went on a family vacation to Barbados with their two children and decided to stay there for eleven years so as to avoid the difficulties of raising a biracial family in the United States during a time when death threats toward biracial families were common. The Attaways returned to California in the late 1970s, where they lived until William Attaway passed away in 1986.

The trajectory of the novel mirrors Attaway’s own life and migration. He was born in Mississippi in 1911 to William S. Attaway, a physician, and Florence Parry Attaway, a teacher. As part of the northward flow during the great migration, his family moved from Mississippi to Chicago when he was six years old to find opportunities in the city and escape the segregated South.

Attaway had little interest in academics as a child. He attended a vocational high school and was set on becoming an auto mechanic. According to various sources, his life changed when he read a poem by Langston Hughes in English class. Not only was he moved, but upon discovering that Langston Hughes was a black poet, he was inspired to apply himself academically and excel throughout the rest of his high school career.

Attaway attended college briefly but was forced to withdraw due to his father’s death. He spent several years traveling and working odd jobs. In 1935 he returned to Chicago and co-authored the Federal Writers’ Project Guide for Illinois. During this time he befriended fellow author and contemporary, Richard Wright. In 1935 Attaway returned to college, completed his degree, and moved to New York.

For a brief time, he continued with several odd jobs including acting, and toured with his sister’s acting troupe for a brief time. He continued to write dramas and novels and send them to publishing houses to elicit interest in his work. His first novel, Let Me Breathe Thunder, was published in 1939. Shortly thereafter he obtained a grant from the Julius Rosenwald Fund to produce his most famous work: Blood on the Forge.

Blood on the Forge, like many novels about the Great Migration, was centered on themes of class struggles and the hardships black American workers faced during the period of the Great Depression. The characters of the three Moss brothers, Big Matt, Chinatown, and Melody, personify the issues of class and race-driven economic disparities of the Depression era. The brothers escape a miserable life as sharecroppers in Kentucky to work in a steel mill in Pittsburgh in anticipation of better wages and working conditions. Instead, they arrive at the mill to find a different set of treacherous conditions that challenge their physical endurance, their dignity, and their spirit. In addition, in the steel mill the men encounter overt hostility from other workers. It turns out that the mill solicited large numbers of black men to come north with the promise of more freedom, improved wages and conditions, but in reality, used them as pawns in an attempt to break a strike organized by current workers, and did not deliver on any of the aforementioned promises. Instead, the brothers faced a hostile work environment with many of the immigrant and white workers who were fearful that this new influx of workers from the South would usurp their jobs.

In a climactic scene there is a race riot at the mill where Big Mat dies and the other two brothers are severely injured. According to Carl Milton Hughes, “Modern tragedy takes into account the failures and frustrations of the life of the ordinary man in highly industrialized civilization. The machine robs man of that sense of immanence that he had in less highly developed epochs” (The Negro Novelist, p. 83). In addition to the rise and fall of man in industrialized society, Attaway utilizes unique character traits in each of the brothers to highlight the decreasing connection between their life and culture as black Americans in Kentucky and their adaptation to life in the North. Big Mat’s brute strength and religious piety no longer suffice as a consolation or raise his spirit in difficult times. Similarly, Melody does not strum his guitar as he used to, and Chinatown’s stories, representative of the oral tradition prominent in Southern black culture, cease to exist as they did when he is blinded in the explosion and can no longer use visual cues to assess his environment.

Blood on the Forge was the last of Attaway’s novels. He later turned to writing for more commercial purposes in radio, films and television. He wrote a number of songs, including the famous “Day-O (Banana Boat Song)” for Harry Belafonte, in whose home he was married in 1962. He married Frances Settele, a white woman, during a very racially charged period in the United States. Several years later, they went on a family vacation to Barbados with their two children and decided to stay there for eleven years so as to avoid the difficulties of raising a biracial family in the United States during a time when death threats toward biracial families were common. The Attaways returned to California in the late 1970s, where they lived until William Attaway passed away in 1986.

Select works by William Attaway:

- Let Me Breathe Thunder, 1939

- Blood on the Forge, 1941

- Calypso Song Book 1957

- Hear America Singing 1967

Select works about William Attaway:

- Hughes, Carl Milton. The Negro Novelist: 1940-1950. The Carol Publishing Group, 1990. New York.

- Vaughan, Philip H. “From Pastoralism to Industrial Antipathy in William Attaway’s Blood on the Forge. Phylon, Vol. 36, No. 4 (4th Qtr. 1975). Pp. 422-425. Clark Atlanta University.

- Waldron, Eward E. “William Attaway’s Blood on the Forge: The Death of the Blues.” Negro American Literature Forum, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Summer, 1976), pp. 58-60. St. Louis University.