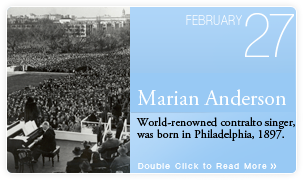

Marian Anderson Born

On this day in 1897 Marian Anderson, who would become a world-renowned contralto singer, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The eldest of three daughters, the family attended the Union Baptist Church in South Philadelphia, taking an active role. At age six, Anderson’s aunt, who was in the choir, noticed her niece’s singing ability and convinced her to join the junior choir. Her aunt also booked her to sing at small functions, earning Anderson 25 or 50 cents a performance. At age 10 she joined the People’s Chorus. Her father died when she was 12, after an accident, forcing the family to move in with her father’s parents. She finished elementary school in 1912, but her family could not afford to send her to high school or for vocal training. Instead, she sought singing instruction wherever she could find it and welcomed any opportunity to improve her singing. After some time, the directors of the People’s Chorus, along with the pastor of her church and other area leaders, came together to raise money for her to attend singing lessons and South Philadelphia High School. Graduating in 1921, she applied to an all-white music school, which rejected her because she was black. She continued private training until 1925, when she won first prize in a singing competition sponsored by the New York Philharmonic. Winning earned her a concert on stage with the orchestra backing. The concert, held August 27, 1925, was critically acclaimed and she remained in New York thereafter to train with Frank La Forge. Despite numerous concerts and appearances in subsequent years, racism in the United States prevented her career from progressing. She began touring in Europe in the 1930s, where she was quite successful. During that time, Sol Hurok became her manager, who would continue as her manager for the rest of her career. In 1935, he persuaded her to return to the U.S. to perform. She first appeared in in New York, and having received highly favorable reviews, began touring the U.S. While she eschewed performing in operas, due to lack of acting experience, many of her aria recordings became bestsellers. She became particularly popular in Scandinavia where “Marian Fever” had spread throughout towns and villages. Even as her fame grew domestically, she still had to deal with being refused food or board in restaurants and hotels. In 1939, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) refused to let Anderson sing in Constitution Hall to an integrated audience. Thousands of members of DAR resigned in protest, including First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Furthermore, Ms. Roosevelt, along with her husband and the NAACP, responded by planning an open air concert at the Lincoln Memorial on the Washington Mall. Occurring on April 9, more than 75,000 people listened to her, in addition to millions who heard her via the radio broadcast. She sang for the troops during World War II and the Korean War, and eventually was invited by the DAR to sing in Constitution Hall in 1943. That same year, she married Orpheus Fisher, an architect. In 1955, Anderson became the first African-American to perform with the Metropolitan Opera in New York, singing Ulrica in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera. This was the only time she played in an opera. In 1956 she released her bestselling autobiography, My Lord, What a Morning. The following year she sang for President Eisenhower’s inauguration and performed in Asia as a U.S. goodwill ambassadress. She later performed at President Kennedy’s inauguration as well. During the 1960s, she supported the civil rights movement, doing benefit performances as well as singing at the March on Washington. In 1963 she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 1964 she began a year long farewell tour, retiring in 1965. She continued to perform occasionally. She won many awards and distinctions over the course of her life, including the UN Peace Prize, Kennedy Center Honors, George Peabody Medal, National Medal of Arts, and a Grammy Award. On April 8, 1993 she died of heart failure at age 96. The famous conductor Arturo Toscanini once said she had a voice “heard once in a hundred years,” a description that has been used association with her talent ever since.